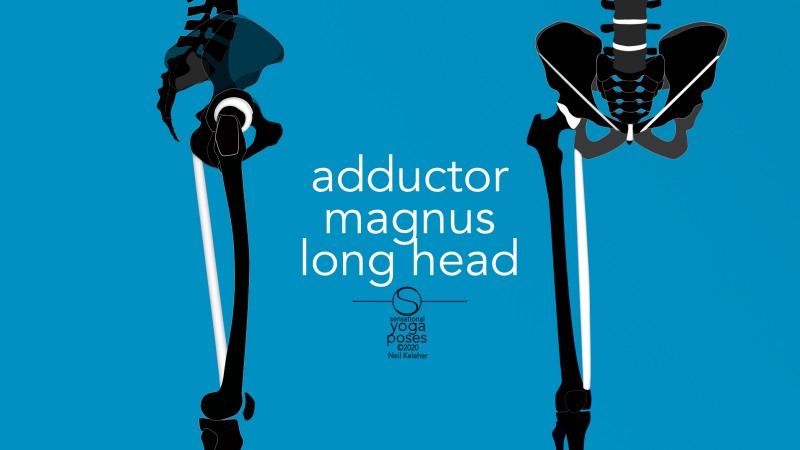

Adductor magnus long head

Helping to stabilize the hip bone relative to the femur

On page cat links

Biceps femoris, Gracilis, Hamstring activation, Hamstrings, Ischial tuberosity, Long hip flexors (sartorius, tensor fascia latae, gracilis), Rectus femoris stretching, Sartorius, Side splits, Splits

In a previous article I talked about the adductor magnus as your back bending friend.

I've also written (but perhaps not yet published) an article about how it can may play a role in the mechanism for stabilizing the shin against rotation. (In this case, it helps to anchor the thigh bone giving the muscles that stabilize the shin a stable foundation from which to work).

In both regards the focus was on using the adductor magnus long head to stabilize or control the thigh bone (or femur) relative to the innominate bone (aka hip bone).

In this article I'll talk mainly about how the adductor magnus long head can be used to help stabilize the innominate bone with respect to the femur.

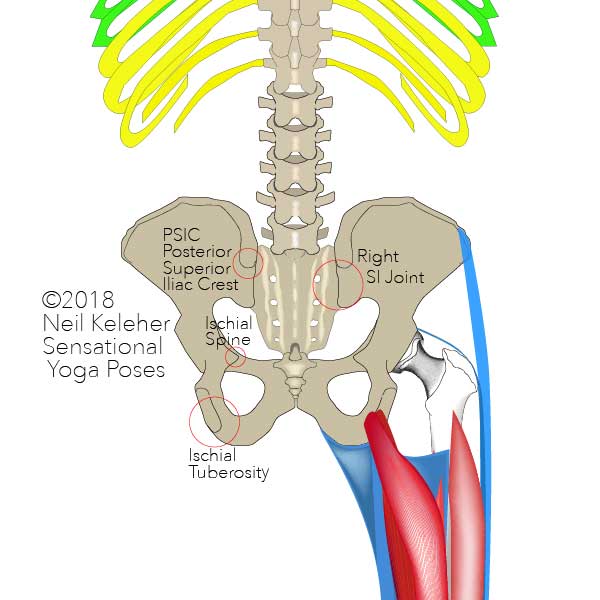

Adductor magnus long head and hamstring upper attachment point

The adductor magnus long head attaches to the ischial tuberosity. This is what most of us normal people think of as the sitting bone (and for those that are even more "normal", those are the bones that you can feel when sitting on a hard chair or on the floor.)

This point forms the bottom rear corner of each hip bone.

The hamstring muscles also attach to the sitting bones.

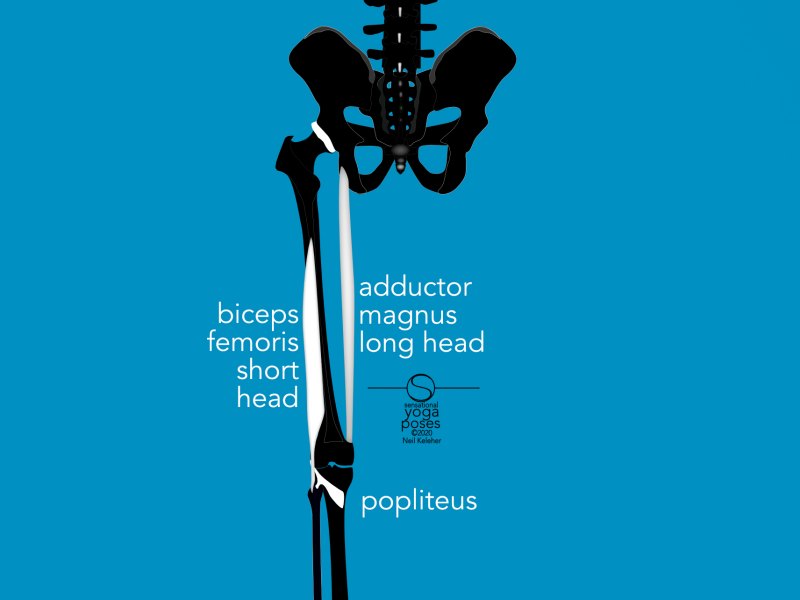

Adductor magnus long head and hamstrings lower attachment point

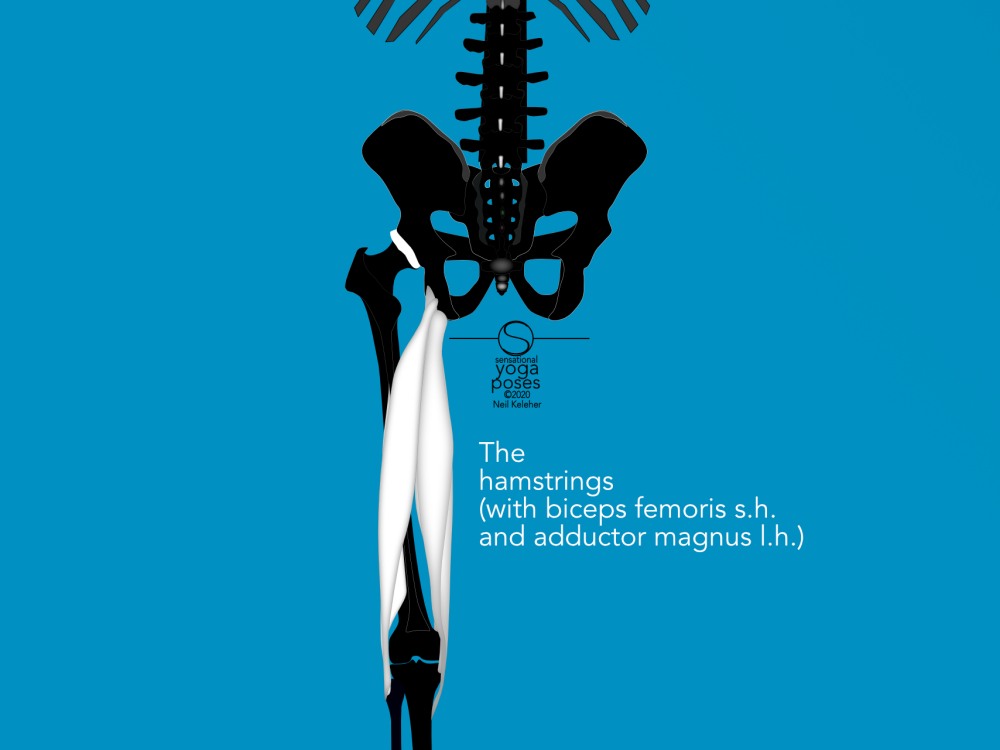

Unlike the long head of the adductor magnus, the hamstrings cross the back of the knee joint.

- The outer hamstrings cross the back of the knee knee joint to attach to the top of the fibula (the smaller of the two lower leg bones which is positioned along the outside of the shin).

- The inner hamstrings attach to the inside of the top of the tibia.

In contrast, the adductor magnus, attaches to the bottom of the inside of the femur, just above the knee joint. So its path is similiar to that of the inner hamstrings, though it may angle forwards a little more prior to attaching the bottom of the femur.

Creating a downward pull on the ischial tuberosity via the hamstrings

To create a downwards pull on the sitting bones the hamstrings have to be working from a stable knee. In particular, for the inner hamstrings to function in this regard, the shin has to be stabilized against internal rotation. In addition, the knee has to be stabilized against bending.

Additionally, the hamstrings also need sufficient length in order to activate effectively. Bending the knee reduces the length of the hamstrings a fair amount as does bending the hips backwards. (The assumption here is that the hamstrings aren't responsible for either the bend of the knee or the bend of the hip.)

In either case (knee bent or hip bent forward), the adductor magnus long head may be an important muscle for creating a downwards pull on the sitting bone, in particular when the hamstrings either aren't anchored or have insufficient length to activate (or when they may be better occupied with other matters such as helping to control the rotation of the shin bones or knee bend).

Pulling downwards and inwards on the ischial tuberosity

Note that because the adductor magnus attaches to the inside edge of the bottom of the femur, and assuming an upright standing position, when it is activated it may tend to create an inwards pull on the sitting bones as well as a downwards pull.

In terms of the whole pelvis, an activated adductor magnus long head will try to turn the pelvis towards the active leg side as well as tilt it back.

If it is active on both legs (while standing symmetrically with weight even on both legs), then the turning force can be neutralized, or converted into an internal rotation force acting on both thighs.

Another option when both legs are active, is that it can tilt the pelvis backwards and at the same time help to counter-nutate the SI joints.

In this case, counter nutation is achieved by pulling the sitting bones inwards towards each other, as well as downwards.

This inwards pull on the sitting bones will then cause the sacrum to tilt back relative to the hip bones.

This is on top of the rearwards tilt that occurs as the pelvis as a whole is tilted rewards.

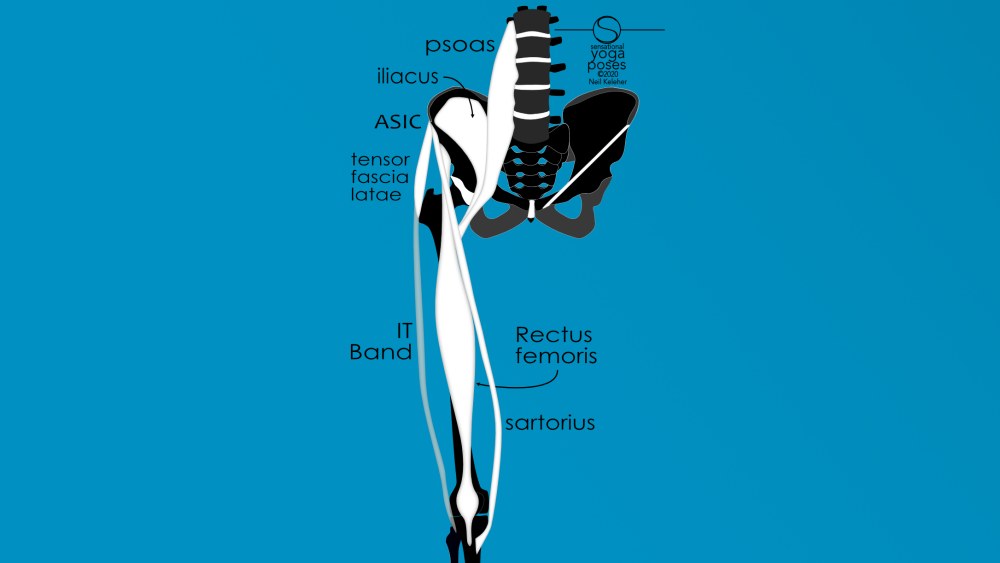

The long hip flexor muscles (Tensor fascial latae, Sartorius, gracilis)

So I mentioned that the adductor magnus long head (along with the hamstrings) attaches to the bottom rear corner of the innominate bone, the ischial tuberosity.

You could think of the ASIC as being located at the opposite corner of the innominate bone from the ischial tuberosity. It is at the front of the upper part of the innominate bone.

The tensor fascia latae, and the sartorius both attach to the ASIC. Rectus femoris also attaches fairly close to this corner point.

All of these muscles can act as hip flexors. Because they act on both the hip and the knee, (and because they are long) I tend to think of them as the long hip flexors.

The gracilis could also be considered a long hip flexor. At the very least it can act to oppose the hamstrings.

The sartorius, gracilis and tensor fascia latae, like the hamstrings, can also act to rotate the shin or help to control shin rotation.

The sartorius

Of the long hip flexor muscles, the sartorius is interesting because with the knee kept straight, this muscle can be used to externally rotate the leg. But it can also, because of its path behind the knee, create an internal rotation force on the tibia relative to the femur.

Note, the sartorius can only do this if the ASIC is anchored. And one way to anchor the ASIC so that the sartorius can work effectively, is to create a downwards pull on the ischial tuberosity.

Anchoring the sartorius for effective activation

One way to anchor the ASIC so that the sartorius can activate effectively is to create a downwards pull on the ischial tuberosity via the hamstrings or adductor magnus long head.

You could also create an upwards pull on the ASICs via the external obliques.

The gracilis

The gracilis, which has a similiar attachment to the tibia but attaches at the upper end to the pubic bone, could create a similiar affect, i.e. it too may also act to externally rotate the femur while internally rotating the tibia relative to the femur.

To anchor it, an upwards pull on the pubic bone would be sufficient.

Stabilizing the femur against rotation via the sartorius and adductor magnus long head

Note that in terms of the femur, the sartorius causes external rotation. The adductor magnus long head tends to cause internal rotation. So in this regard these muscles also compliment each other.

With the femur rotationally stable, and anchored at the ASIC, the sartorius can create an internal rotation force on the tibia which can be resisted by the biceps femoris long head or, perhaps more likely in this scenario, by the biceps femoris short head.

Bringing in the biceps femoris

The upper end of the biceps femoris short head attaches to the back of the femur and from there, reaches down to attach to the top of the fibula. It tends to try to rotate the shin externally relative to the femur. However, with the shin stable, it can rotate the femur externally relative to itself.

Focusing on the knee, the internal rotation force that the sartorius creates on the tibia can work against the external rotation force on the tibia created by the short head biceps femoris. Together these forces can help to stabilize the shin against rotation at the knee joint. This in turn can help to anchor muscles that work from the shin on the bones of the feet.

Generally this can make it easier to maintain the arch of the foot, preventing it from collapsing.

Using the adductor magnus long head for anchoring the spinal erectors

Another scenario that the adductor magnus long head can be useful is in an exercise like the bench press.

Anchoring the spinal erectors while bench pressing

Because the knees are generally bent, it can be hard to use the hamstrings to create a "downwards" pull on the sitting bones. (Okay, you are lying down so actually, it would be a pull towards the knees.)

Why create a downwards pull on the sitting bones? To anchor the spinal erectors that attach from the back of the hip bones to the backs of the ribs (iliocostalis.)

If these muscles are anchored and can activate, they can create a downwards pull on the backs of the ribs (pulling towards the back of the hip bones) which can be resisted by activating the obliques (or even better, by activating the transverse abdominis so that the obliques activate). This stabilizes the ribcage helping to anchor the muscles that attach from ribcage to scapulae and or clavicle.

So, if you are wanting to use this activation, creating a downward pull on the sitting bone can be achieved by using the adductor magnus long head.

Anchoring the sitting bones while doing a military press.

In a standing weight lifting exercise like the military press, the knees are straight.

While you could use the hamstrings to create a downward pull on the sitting bones, you could also use the adductor magnus.

As with the bench press, this can help to anchor the spinal erectors that act on the back of the ribs. In turn, the abs can be activated to help stabilize the elements of the torso giving the muscles that control the shoulder blades (and collar bones) a foundation from which to help control those bones, thus in turn giving the shoulder muscles a stable foundation from which to work on the arm bones.

Anchoring the sitting bones in a standing forward bend

Another situations where adductor magnus long head activation may be helpful is in a standing forward bend.

One possibility here is that with the adductor magnus creating a downwards pull on the sitting bones, the hamstrings can be relaxed and stretched. (The adductor magnus can also be stretched while active.)

Note, that if you can feel and control the adductor magnus as well as the hamstrings, and can differentiate them, then this is something you can at least try to see how effective it is or isn't.

Bent knee hip flexor stretches and the adductor magnus long head

Adductor magnus long head activation may be beneficial in bent knee hip flexor stretches like couch stretch.

In this case, the activation of adductor magnus long head can help to provide an anchor for the rectus femoris, which is the main muscle being stretched when you stretch the hip flexors with knee bent. By anchoring it, you may make it easier for it to lengthen (whether it is active or relaxed.)

Controlling the ischial tuberosities in side splits

For side splits, activating the adductor magnus long head can be as simple as creating an outwards pull on the sitting bones.

Note that in side splits, depending on foot position (knees pointing upwards so that feet point up or knees pointing forwards so that you can try to get feet flat on the floor) you might choose to pull the sitting bones inwards first in order to counter-nutate the sacrum.

Counter-nutating the sacrum in side splits

In counter-nutation, the sitting bones move inwards while the ASICs move outwards and in side splits, this may help to prevent the top of your thigh bone from impinging on the side of the hip bone.

And so you could try nutating the sacrum by pulling inwards on the sitting bones using the pelvic floor muscles.From there you could activate the adductor magnus long head.

Note that in this case, you could think of the activated pelvic floor muscles as helping to anchor the adductor magnus long head by creating an inwards pull on the ischial tuberosities.

Nutating the sacrum in side splits

You can also try sacral nutation. In this case you might choose to stabilize the knee joint (and thus the femur) so that the bottom end of the adductor magnus is anchored. It can then be used to pull the sitting bones outwards and thus help nutate the sacrum.

Note that standing upright with feet close together, the adductor magnus long head can be used to help pull the ischial tuberosities inwards.

However, with legs apart, or adducted, as in side splits, activation of the adductor magnus long head can cause the sitting bones to spread apart instead.

How do you know whether you should nutate or counter-nutate?

Whether nutating or counter nutating the sacrum, the idea is to "ideally" position the femur relative to the hip bone as you work your way deeper into side splits.

So that you can determine for yourself at any moment in time which option is best, it helps if you can feel your hip bones, sacrum, femur, and the muscles (and ligaments) that help control the relationships between these elements.

As a rough guideline, if your lumbar spine is bent backwards, then spread your sitting bones to nutate your sacrum. If it is reasonably flat (or bent forwards) then try retracting your sitting bones to counter-nutate

Front splits

In front to back splits, you could experiment with activating adductor magnus long head for the front leg and/or the back leg. If nothing else, you may get better hip stability which may then allow you to go deeper into the splits.

Front leg

For the front leg, you could try anchoring the knee (make it feel "strong") and then from there create an inwards pull on the front leg sitting bone to activate the adductor magnus long head.

Back leg

For the back leg, you could try activating your spinal erectors first. Use them to bend your spine backwards (and create a downwards pull on the backs of your ribs). Work at spreading your sitting bones as you do this.

From there, work at activating the adductor magnus long head of the back leg. Try pulling the back leg inwards slightly (or generate an "inwards" pull on the knee of the back leg). Also try creating an internal rotation force at the inside of the knee as it trying to keep the back knee pointing downwards.

Getting a taste of muscle control

Note that the goal of this article isn't to say which muscles are most important. Instead, it's to give you a hint of the necessary understanding so that you can explore these options for yourself. To get more than a hint of understanding it helps if you learn to directly experience these muscles in your own body.

The nice thing about muscle control in general is that because it allows you to feel particular parts of your body, it gives you the tools for assessing for yourself whether a particular muscle control action is helpful or not.

Published: 2020 08 15

Updated: 2023 03 23