Sacrotuberous Ligament, TOC

Because the sacrotuberous ligament runs downwards from the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity, then when the sacrum moves downwards, tension in the ligament is potentially reduced. When the sacrum moves upwards, tension in the ligament is increased.

This assumes that the ligament is passive.

Because the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament runs upwards from the sacrum to the PSICs, when the sacrum moves upwards, tension in the ligament is reduced while when the sacrum moves downwards, tension in the ligament is increased.

This again assumes the ligament is passive.

Another way to look at it is that when the sacrum moves upwards relative to the hip bones (nutation), tension in the sacrotuberous ligament is increased while tension in the long dorsal sacroiliac ligaments is decreased.

The opposite happens when the sacrum moves downwards (counter-nutation) relative to the hip bones.

Both ligaments can be actively tensioned to help control the position of the sacrum relative to the hip bones. As a result they can help to stabilize the SI joints through their entire ranges of motion, not just at the end points.

With an understanding of the muscles that directly or indirectly add tension to these ligaments, you can use muscle control to help stabilize one or both SI Joints via the sacrotuberous and long dorsal sacroiliac ligaments.

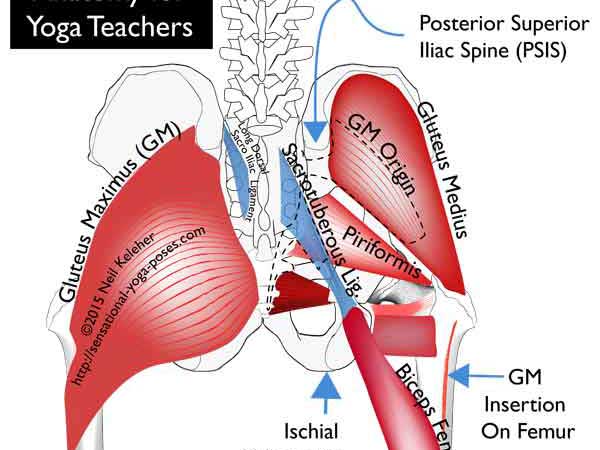

The Sacrotuberous Ligament runs downwards and laterally outwards from the rear of the sacrum to the Ischial Tuberosity (IT).

Via muscle activation, it can be used to create a downwards pull on the sacrum or resist an upwards pull.

Muscles whose fibers blend with or partially make up the fibers of the sacrotuberous ligament include:

- the Piriformis,

- Gluteus Maximus and

- Biceps Femoris (long head).

The Long Dorsal Sacroiliac Ligament connects upwards from the sacrum (from the third and fourth segments) to the Posterior Superior Iliac Spine (PSIS).

Via the muscles that act on it, it can create an upwards pull on the sacrum (relative to the hip bones) or resist a downwards pull.

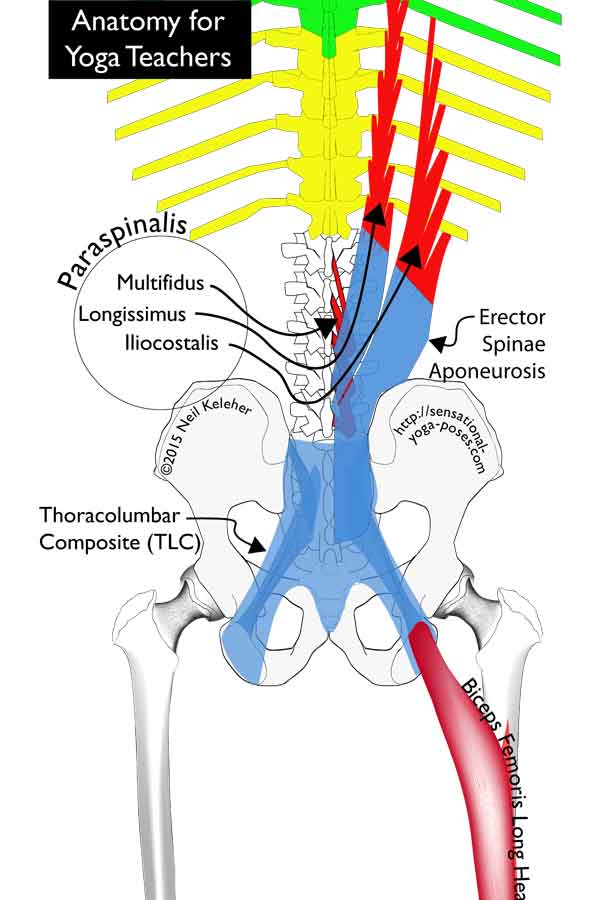

It connects to the Paraspinal Rectinacular Sheath and the aponeurosis of the Erector Spinae. It has attachments to the lumbar portion of the thoracic longissimus. It also connects to the multifidus. The more medial fibers of the ligament also connect to aponeurotic fibers of the latissimus dorsai.

Below the PSIC, the ligament is connected to (and covered by) the fascia of the gluteus maximus.

Laterally, at its lower extent, its fibers which are continuous with those of the sacrotuberous ligament.

Both the piriformis and the gluteus maximus have fibers that blend with the sacrotuberous ligament.

Tension in either muscle can be used to add tension to the sacrotuberous ligament when the sacrum is counter-nutated.

The Piriformis attaches to the front surface of the sacrum and from there passes forwards, downwards and outwards to attach to the thigh bone.

Assuming the femurs are fixed, then activating the piriformis creates a downwards (and forwards) pull on the sacrum. This could induce a reduction in tension in the sacrotuberous ligament. However, tension in the fibers of the piriformis that blend with those of the sacrotuberous could make up for the loss.

Because the Piriformis attaches to the sacrum below the SI joints, activation of the piriformis could pull the sacrum into counter-nutation, a backward nodding of the sacrum relative to the hip bones.

Counter-nutation is when the bottom tip of the sacrum moves forwards, towards the pubic bone. At the same time, the top of the sacrum moves rearwards. The back of the sacrum could be thought of as moving downwards relative to the hip bones.

Additionally, with counter nutation the ASICs move outwards and the ischial tuberosities inwards causing the top of the pelvis to slightly widen and the bottom of the pelvis to slightly narrow.

The opposite movement is nutation.

Nutation is where the sacrum nods forwards relative to the hip bones so that the top of the sacrum moves forwards relative to the hip bones and the bottom tip moves rearwards, away from the pubic bone.

Here, the back of the sacrum could be thought of as moving upwards relative to the hip bones.

In this case, the ASICs move inwards and the ischial tuberosities move outwards.

The Gluteus Maximus (GM) has attachments to the rear of the sacrum, and portions of the rear of the pelvis. It also has fibers that attach to (or blend with) those of the sacrotuberous ligament.

And it has attachments to the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament.

The gluteus maximus can be activated to cause extension of the hip joint (moving the femur rearwards) or to resist or brake flexion of the hip joint. Assuming this latter case, fibers of the gluteus maximus that attach to the sacrotuberous could activate along with other fibers. This would add tension to the ligament helping to stabilize the SI joint by resisting nutating forces.

The gluteus maximus also has attachments to the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament. So not only can it resist nutating forces, it can also resist counter nutating forces. Thus it could help to keep the SI Joint stable whether the leg is moving forwards or rearwards.

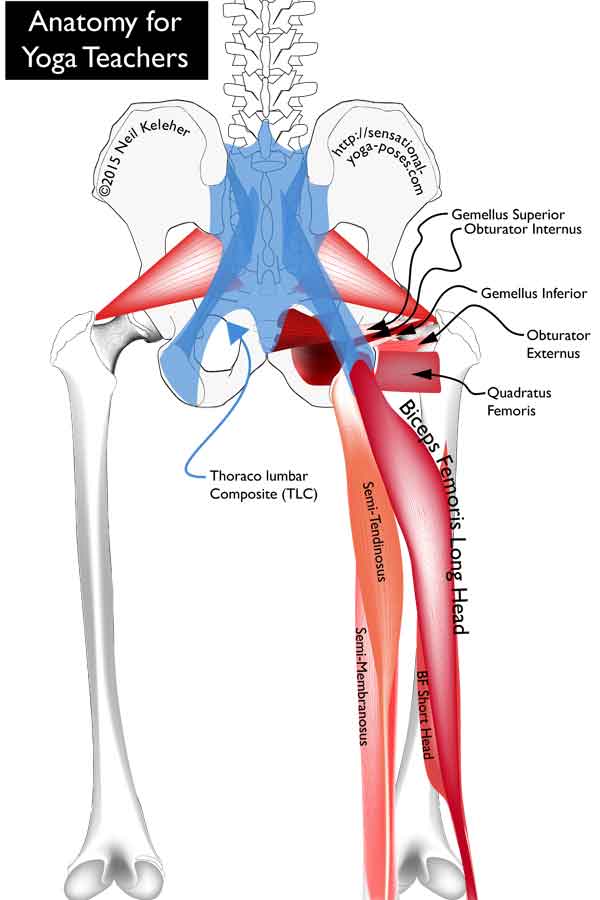

The Biceps Femoris (long head) unlike the other hamstrings (the Semitendinosus and Semimembranosus) often attaches directly to the sacrotuberous ligament without attaching to the ischial tuberosity (IT).

Note that fibers the sacrotuberous ligament that are continuous with the biceps femoris tend to attach to the lower portion of the sacrum. So while tension in the biceps femoris can add tension to the sacrotuberous ligament, it does so in such a way that it doesn't cause nutation.

In a standing forward bend with the pelvis tilted forwards relative to the femurs, the weight of the upper body acting via the spine can create a force that tends to pull the sacrum cranially (towards the head). These forces could be thought of as nutating forces.

If the hamstrings are activated (even as they are being stretched by the forward tilt of the pelvis), they can add tension to the sacrotuberous ligament. While this doesn't directly help to resist further nutation of the sacrum, it can help to add enough tension to the sacrotuberous ligament to give the fibers of the gluteus maximus and/or the piriformis an anchor from which to act. These fibers can then activate in such a way as to resist nutation and stabilize the SI Joint.

To further stabilize the SI joint with the sacrum counter-nutated, (or to cause counter-nutation in the first place) the pelvic floor muscles could also activate. Quite probably these would activate prior to the piriformis activating. They could be used to initiate the inward movement of the ITs and the forward movement of the bottom tip of the sacrum, with the piriformis coming into play once the action has been initiated.

Note that the pelvic floor muscles can be used with the sacrum nutated to help resist the forces causing nutation. Whether the sacrum is nutated or counter-nutated, the opposing forces would help to stabilize the SI joints.

An important consideration is that for any muscle to activate it needs an opposing force to work against.

So for the above mentioned muscles to actively pull the SI Joints into nutation, there needs to be an opposing force that resists nutation.

This opposing force could come from body weight. It could come from opposing muscle action.

In either case, the opposing forces are what help to create stability.

For more on the requirements for muscle activation, read Muscle Control Principles

Muscles that can add tension to the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament and thus help it to actively cause nutation include the lumbar multifidus, the latissimus dorsai and the lower fibers of the transverse abdominis muscle.

The lumbar multifidus (and lumbar spinal erectors) can be used nutate the sacrum so that it nods forwards relative to the hip bones.

The Long Dorsal Sacroiliac Ligament could also play an active roll in nutation since contraction of the Erector Spinae leads to additional tension in this ligament so that it acts in creating an upward pulling force on the rear of the sacrum which leads to nutation.

In this instance the ligament acts more in the manner of a tendon than in the way we normally conceive a ligament would act.

In experiments where traction was used to simulate the action of the latissimus dorsai, this resulted in a reduction of tension in the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament.

In this case the simulated force of latissimus dorsai helped to nutate the sacrum. As a result tension was reduced in the long dorsal ligament.

With tension reduced in the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament, the opposite would happen in the sacrotuberous ligament. Tension would be increased.

The lower fibers of the latissimus dorsai cross the midline of the body to connect with fibers of the opposite gluteus maximus. Activating together, these can act to help stabilize the SI joints in such a way that tension in the long sacroiliac tendon is superfluous.

While pressing or pulling inwards on the ITs causes counter nutation, a pulling inwards on the ASICs via the lower fibers of the Transverse Abdominis can cause the ITs to move outwards. This same action creates a tendency for the PSIS, which are behind the SI joints, to move apart. This outward lateral movement of the PSISs is resisted by the Thoracolumbar Composite.

The Thoracolumbar Composite spans the PSIS on both sides as well as attaching to the rear of the sacrum, Long Dorsal Sacroiliac and Sacrotuberous ligaments. It resists any tendency of the PSIS to move outwards and when the Transverse Abdominus are activated it actually helps to compress the SI Joints.

With the transverse abdominis activate and creating an inwards pull on the ASICs, the Ischial tuberosities tend to move outwards. This can be resisted by activation of the pelvic floor muscles. Working against each other, the forces from the pelvic floor muscles and the lower fibers of the transverse abdominis can help to stabilize the SI Joints. In this case, tension in the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament isn't required, since the SI joint is already stable.

Hip muscles that can cause nutation include the Iliacus and Obturator Internus.

The Iliacus, could help to pull the ASICs inwards, acting in the same way as the Transverse abdominus. Lack of leverage might be made up by an increased contact area of the iliacus.

Obturator internus, like the iliacus, attaches to a large surface area on the inner surface of the innominate bone.

It's tendon passes out through the lesser sciatic notch, wraps around the pelvis and attaches, like the piriformis, to the inner surface of the greater trochanter just above the neck of the thigh bone.

Assuming that the femurs are stabilized against external rotation (and perhaps even slightly internally rotated) the obturator internus could activate in such a way as to help pull apart the ITs, adding tension to the Sacrotuberous Ligaments.

Actual nutation of the sacrum could then be carried out by the sacral multifidus.

Note that one possible consequence of using the obturator internus to add tension to the sacrotuberous ligament is that it could give the fibers of the Gluteus Maximus that attach to it a firm foundation from which to act on the thigh bone.

This could be important in extreme hip flexion. The gluteus maximus could then have extra fibers to recruit to help pull the body out of hip flexion if needed.

In addition this could also give the biceps femoris a more stable anchor to assist the gluteus maximus in pulling the hips out of flexion.

As shown above, there are a number of options for creating nutation and counter-nutation both.

While some papers suggest that nutation is the more stable position I would suggest that the muscles of the pelvis and hip (and back) can function in such a way to stabilize the SI joint through a full spectrum of positions. So rather than just being stable when fully nutated or counter nutated, the muscles that create these actions can be used against each other (or against body weight) as an option for creating stability in any of the in-between positions of the SI Joint.

The muscular control of the Sacrotuberous and Long Dorsal Sacroiliac Ligaments offers a few possible mechanisms for creating this stability.

- One possibility for stability is to use the Transverse Abdominus against the pelvic floor muscles.

- Another possibility is to use the hip muscles against each other.

- There may also be combinations of pelvic muscle and hip muscle activation that naturally stabilize the si joint.

One possible sequence is to first activate transverse abdominus and pull inwards on the ASISs. Then gluteus minimus and/or TFL have a stable foundation from which to act on the femurs and/or the tibias, internally rotating them or stabilizing them against external rotation. The Obturator Internus could act from the femurs to pull outwards on the ITs.

To help in understanding how different muscles can act on the SI joint via the sacrotuberous and long dorsal sacroiliac ligament it can help to understand that both are connected to a connective tissue complex called the Thoracolumbar Composite.

The thoracolumbar Composite is part of the Thoracolumbar Fascia.

Published: 2015 10 01

Updated: 2023 03 22