Thoracolumbar Fascia, TOC

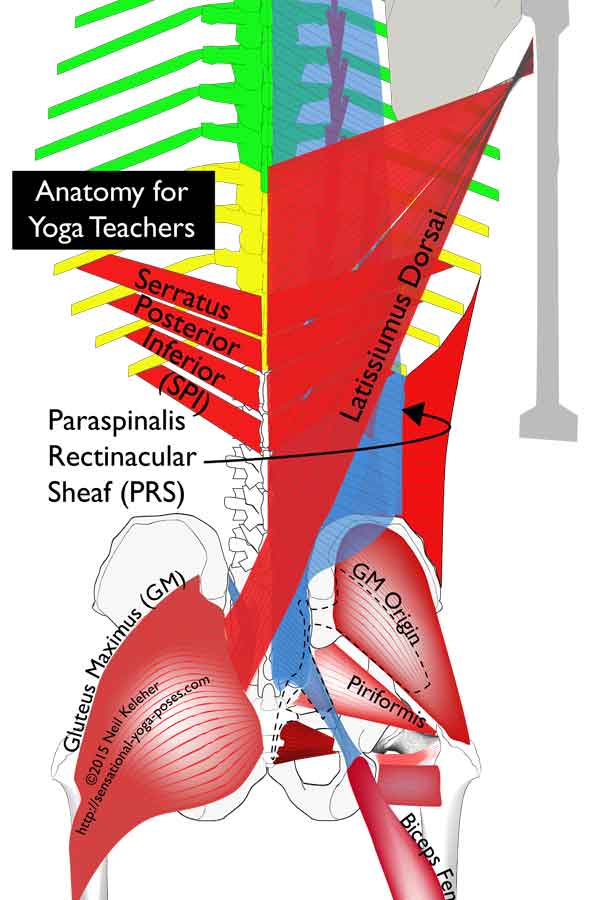

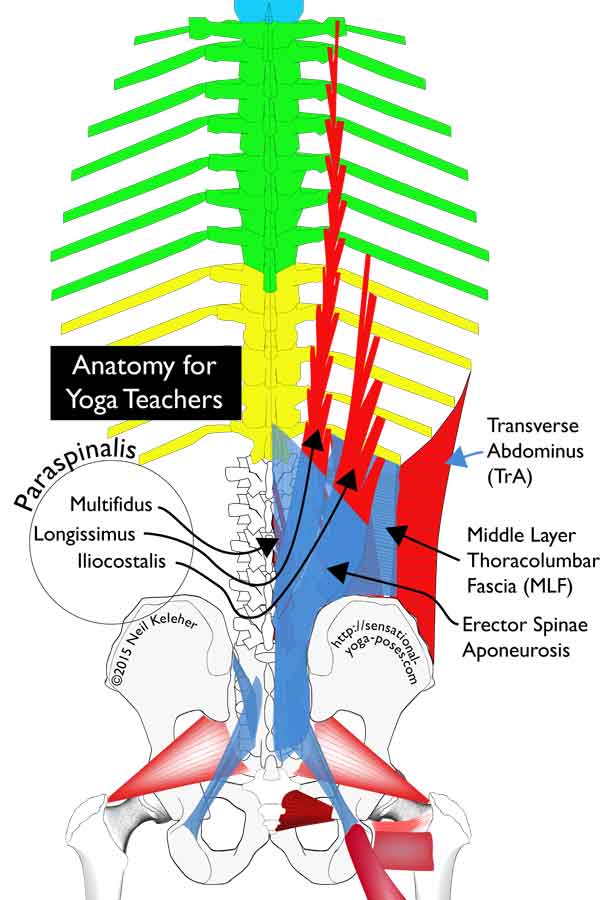

One of the main components of the thoracolumbar fascia is the Paraspinalis Rectinacular Sheath or PRS.

The Paraspinalis Rectinacular Sheath (or PRS) is the composite sheath of connective tissue and bone that wraps around the Erector Spinae and Multifidus muscles.

The posterior layer is relatively continuous, extending from the back of the sacrum all the way up to the base of the skull.

The anterior layer is a bit more interesting. It starts from the top of the sacrum (where it connects to the joint capsules of the two SI Joints). From there it reaches upwards to connect to the lowest set of ribs (the 12 ribs). This portion is made up in part of fibers from the Transverse Abdominis.

From the bottom of the ribcage upwards, the anterior layer is made up of the backs of the ribs and then from there from the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae.

In the lumbar region the PRS can be divided into two different connective tissue portions, a front wall and a back wall.

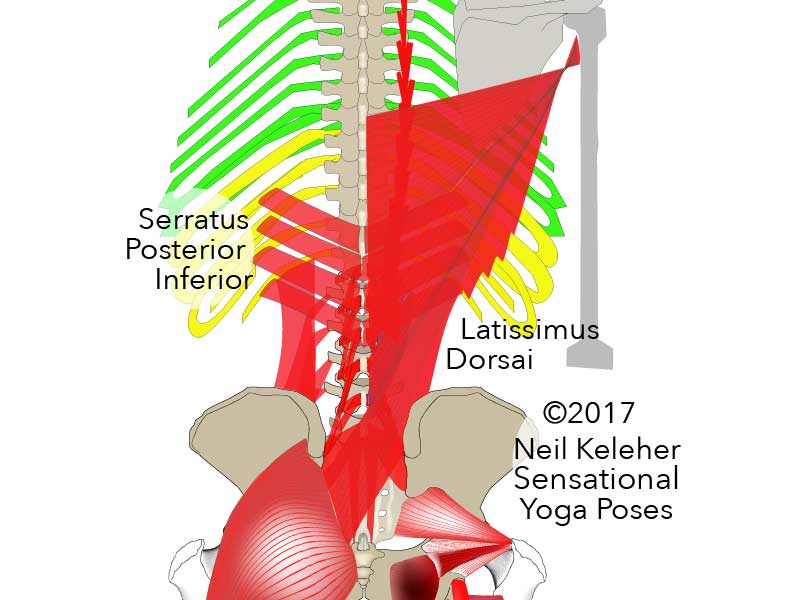

Before talking about either of those, both the Latissimus Dorsai and the Serratus Posterior Inferior and bear mentioning with respect to how they tie in to and affect the thoracolumbar fascia.

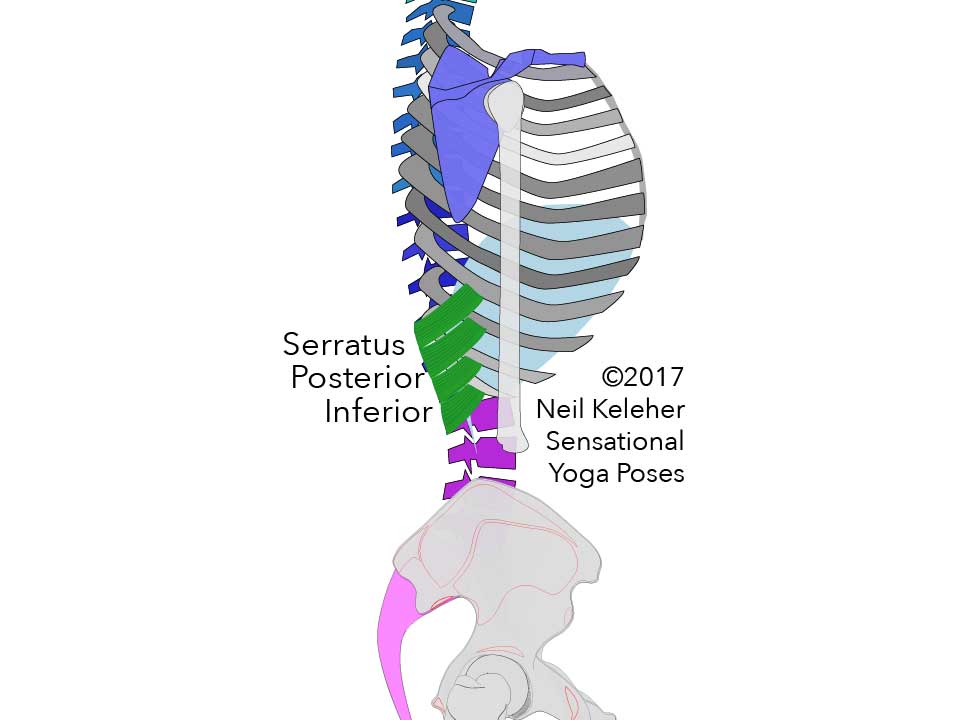

The serratus posterior inferior or SPI is thin muscle that connects to the four lowest ribs.

It's made up of four "sheets of muscle" or fascicles that form a set of downward pointing arrowheads. The tips of these arrowheads connect to the spinous processes of the lower two thoracic vertebrae and the upper two or three lumbar vertebrae.

Crossing the back of the body behind the back wall of the paraspinalis rectinacular sheath, the aponeurosis (or "tendon-like" structure) of the serratus posterior inferior fuses with the back wall of the PRS about midway between the lateral and medial borders of the PRS.

Since the SPI crosses the thoracolumbar junction, one of it's roles can be in helping to stabilize this region.

How the Serratus Posterior Inferior Interacts with the Thoracolumbar Fascia?

Assuming that the lower ribs are being pulled upwards, the serratus posterior inferior can be used to exert an upwards pull on the posterior wall of the lumbar portion of the PRS.

This could be useful when backbending (extending) the spine. It could also help in resisting any backbending of the thoracolumbar junction.

If the back wall of the PRS is suitably anchored, then the back wall of the PRS could act as an anchor to aid the SPI in creating a downwards pull on the lower four ribs.

How the Serratus Posterior Inferior Interacts with the Transverse Abdominis

Another important aspect of the Serratus Posterior Inferior is that it may act in opposition to the upper fibers of the transverse abdominis. Namely it can oppose these fibers when both sets of muscles are activated to help stabilize the thoracolumbar junction.

Acting against the upper transverse abdominis, it can help that muscle to protect the solar plexus against impact.

How the Serratus Posterior Inferior Might Interact with the Respiratory Diaphragm?

Both the Serratus Posterior Inferior and the respiratory diaphragm attach to the upper two or three lumbar vertebrae.

These two sets of muscles can work in opposition to help stabilize the upper lumbar vertebrae.

Tension in the diaphragm, as well as in the upper transverse abdominis as well as the SPI may help to further protect the Solar Plexus against impact, as mentioned above.

At its upper point of attachment, the latissimus dorsai attaches to the front of the upper arm, near the ball of the shoulder joint. From here the various fibers of the latissimus dorsai attach to the spine, ribs and hip bones as follows:

- The upper fibers of this muscle attach to the spinous processes of the lower six thoracic vertebrae.

- The next set of fibers connect to the spinous processes of the upper two lumbar vertebrae.

The fibers that attach to the upper two (or three) lumbar vertebrae can glide relative to the PRS due to the intervening layer of the Serratus Posterior Inferior.

- Next, the Raphe, fibers of the latissimus dorsai attach to the spinous processes of the lower three lumbar vertebrae after first attaching to the lateral raphe.

The lateral raphe marks the boundary where the transverse abdominis attaches to the paraspinalis rectinacular sheath.

- The Iliac fibers connect to the iliac crest.

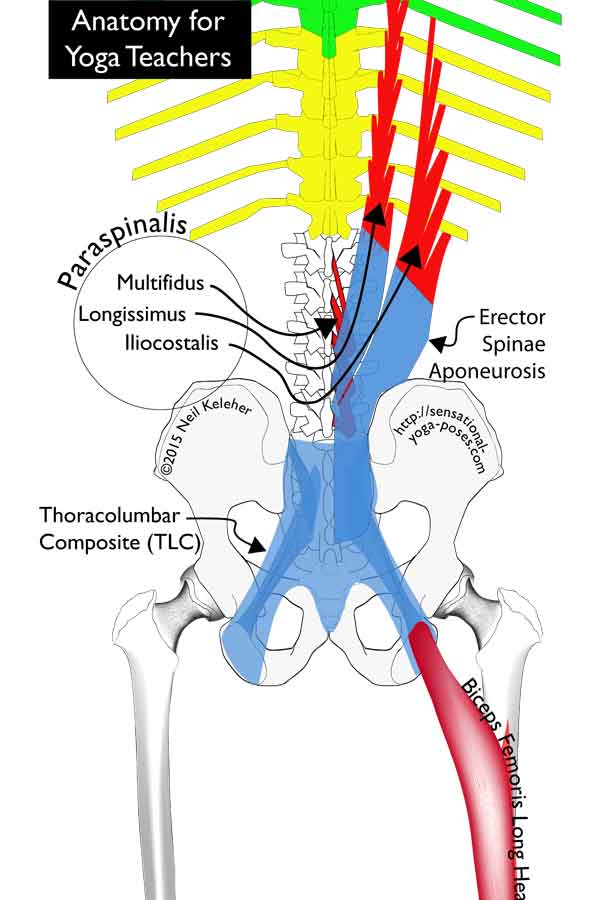

The iliac fibers cross the back of the sacrum to blend with fibers of the opposing side Gluteus Maximus. These fibers are fused with the back layer of the PRS as well as the erector spinae aponeurosis to help form the thoracolumbar composite.

- Finally, the Costal fibers of the latissimus dorsai attach to the lowest two or three ribs.

The Latissimus Dorsai and the SI Joint

Probably the most important relationship the Latissimus dorsai has with the thoracolumbar fascia is where the iliac fibers cross the midline of the body at the level of about L5 and the sacrum to connect to fibers of the opposite side gluteus maximus.

These fibers are fused with underlying layers of fascia to form the Thoracolumbar composite.

Combined activation of the latissimus dorsai and the opposing gluteus maximus (in particular the superficial fibers of the gluteus maximus) may help in SI Joint stabilization on the same side as the active gluteus maximus, since fiber direction of both sets of muscles is relatively perpendicular the the SI Joint.

The Latissimus Dorsai and the Thoracolumbar Composite

Because the iliac fibers of the latissimus dorsai are part of the fused mass of connective tissue called the thoracolumbar composite, then tension in the latissimus dorsai and the opposing superficial gluteus maximus fibers may not just help to stabilize the sacrum, they may also help to further stabilize the thoracolumbar composite (if it needs further stabilizatoin).

This could then provide anchoring for the PRS as well as the erector spinae aponeurosis, thus helping to anchor the spinal erectors and multifidii in the sacral and lumbar region.

The Latissimus Dorsai, the Lateral Raphe and the SPI

The latissimus dorsai also has attachments to the lateral laphe which marks where the transverse abdominis joins with the PRS.

Below the bottom border of the serratus posterior inferior, the aponeurosis of the latissimus dorsai blends with the back wall of the PRS via the lateral raphe.

Thus the latissimus dorsai may be able exert a lateral pull on this portion of the PRS which may help in twisting or rotational movements of the spine.

But if the PRS is suitably anchored, then the PRS can act as an anchor for the latissimus dorsai allowing for stronger pulling actions.

The Latissimus Dorsai and the Serratus Posterior Inferior

Above its lower border, the serratus posterior inferior comes between the latissimus dorsai and the PRS. However, the SPI attaches to the lower four ribs while the latissimus dorsai has attachments to the lower two or three ribs.

As such, assuming that the bottom of the serratus posterior inferior is anchored sufficiently, then the serratus posterior inferior can create a downwards pull on the lower ribs helping then to anchor the fibers of the latissimus dorsai that attach to those ribs.

Or conversely, the lats can help to anchor the SPI which in turn could also help in twisting actions in the region of the thoracolumbar junction.

The posterior wall of the PRS is sometimes termed The Deep Lamina of the thoracolumbar fascia.

It extends all the way up the back of the spine, from the back of the sacrum to the base of the skull.

As noted above, in the sacral and lower lumbar region, the posterior wall of the PRS is fused with common shared fibers of the latissimus dorsai and the opposite side gluteus maximus.

In the upper lumbar region, the posterior wall fuses with the overlying anoneurosis of the serratus posterior inferior.

In the region of the cervical spine, the back wall of the PRS blends with the deep fascia of the splenius neck muscles.

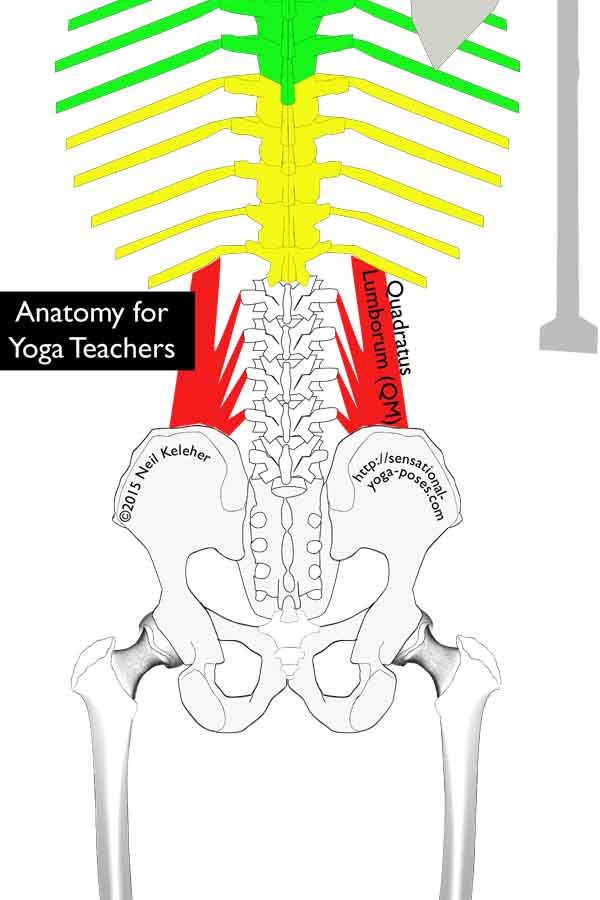

In the lumbar region the front wall of PRS passes between the spinal erectors and quadratus lumborum to attach to the transverse processes of the lumbar spine.

The front wall is made up of fibers from both the aponeurosis (tendon like structure) of the transverse abdominis and from the fascia (posterior epimysium) that covers the back surface of the quadratus femoris.

Because of this, the front wall of the paraspinalis rectinacular sheath is thicker than the back wall.

The Middle Layer of the Thoracolumbar Fascia

In the lumbar region, the front wall of the paraspinalis rectinacular sheath is sometimes referred to as the MLF which stands for Middle Layer of the thoracolumbar Fascia.

Because this layer is made up of fibers from both the transverse abdominis and the quadratus lumborum, it can be affected by changes in muscle activity in either.

The Transverse Abdominus creates a seam where it connects to the PRS. This seam is called the Lateral Raphe and it extends between the iliac crest and the bottom of the 12th rib (the lower most rib).

Lumbar Interfascial Triangle (LIFT)

In the lumbar region, the inner surface of the PRS is relatively seamless. i.e. there is no seam that shows the division between the front and back walls of this structure. However, externally the anterior and posterior walls of the PRS separate from this "inner layer" before joining together just before the lateral raphe. Thus a triangular structure is formed.

This triangular structure is called the Lumbar Interfascial Triangle or LIFT.

Distributing Tension from the Abdominal Muscles to the PRS

One possible reason for Lumbar Interfascial Triangle is that it allows the lateral raphe to distribute tension from the abdominal muscles (particularly the transverse abdominis, but also the internal obliques) to both the anterior and posterior walls of the PRS. This would be despite the spine backward bending, forward bending etc.

Since the latissimus dorsai has attachments to the lower portion of the Lateral Raphe, the lumbar interfascial triangle may also act to help distribute tension from it to the front and back walls of the PRS.

In the lumbar region the Paraspinalis Rectinacular Sheath wraps around three sets of muscles. Those three sets of muscles are:

- the longissimus,

- iliocostalis (both erector spinae muscles) and

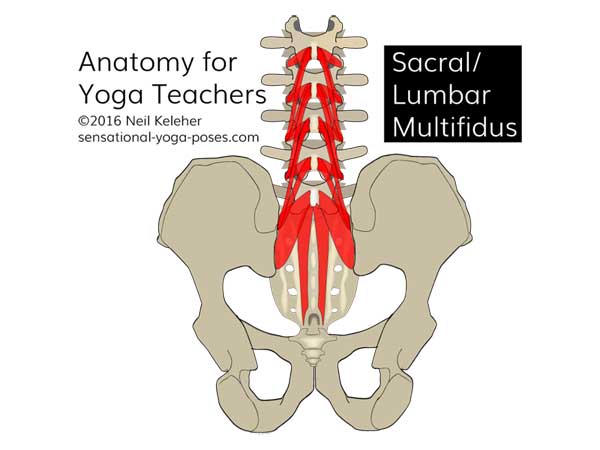

- the multifidus (part of the transversospinalis group.)

Within the PRS is the shared aponeurosis of these three muscles, the Erector Spinae Aponeurosis.

Despite being called the Erector Spinae Aponeurosis, this aponeurosis actually connects to all three muscles (so the multifidus, which isn't a spinal erector, also) in the lumbar region.

It's positioned to the rear of these muscles so that they all attach to its front surface.

The Extent of the Erector Spinae Aponeurosis

The upward pointing arrow shape of the spinal erector aponeurosis reaches high into the thoracic region close to the spine. More laterally it only reaches up to about the height of the bottom of the third lumbar vertebrae.

Extending upwards from the sacral region, this aponeurosis covers the entirety of the back surface of the lumbar multifidus as well as the base of the iliocostalis and longissimus muscles.

These latter two muscles are generally referred to as part of the spinal erectors

In the lumbar region the aponeurosis is only loosely connected to the PRS meaning it has some ability to move relative to the PRS

In the region of the L5 (the lower most lumbar vertebrae) and the sacrum , the erector spinae aponeurosis is fused with the posterior layer of the PRS as well as the more superficial layers of the thoracolumbar fascia, generally portions of the aponeurosis of the Latissimus Dorsai, to form a composite structure called the Thoracolumbar Composite.

The Thoracolumbar Composite spreads downwards to cover the sacrotuberous ligaments, in the process connecting to the gluteus maximus muscle.

Higher up, the Thoracolumbar Composite connects laterally to the back part of the iliac crests at each PSIC.

Preventing Lateral Spreading of the PSICs

Along with the Long Dorsoiliac ligament (or long dorsal sacroiliac ligament), the TLC resists any lateral spreading apart of the two PSIS.

This resistance to spreading may be augmented by activating the lumbar multifidus since when active they help to pump up the TLC, increasing its tension and thus its resistance to spreading of the two PSICs.

The lumbar multifidus begins at L1, attaching to the backs of all the lumbar vertebrae and further extending all the way down the back of the sacrum.

The Gluteus Maximus and the TLC

The gluteus maximus connects, in part, to the thoracolumbar composite as well as the sacrotuberous ligament. As mentioned, fibers from the thoracolumbar composite are continuous with those of the sacrotuberous ligament.

Because of this, tension in the thoracolumbar composite, which could come from the Latissimus dorsai or any of the paraspinalis muscles, could help to anchor the attached gluteus maximus fibers so that they in turn can activate effectively to extend the thigh and/or add tension to the back edge of the iliotibial band.

If the shin and femur are stable, and the gluteus maximus is active, then it can act to anchor the thoracolumbar composite helping to give the paraspinalis and/or latissimus dorsai a stable anchor point to act from.

The Hamstrings and the TLC

The hamstrings, and in particular the biceps femoris long head, connect to the sacrotuberous ligament which as mentioned is part of the Thoracolumbar composite.

Stabilizing the thoracolumbar composite either via the paraspinalis, latissimus dorsai or both, the hamstrings would have an stable anchor point from which to act on the back of the hip joint and knee joint.

If instead the shin (in particular, the fibula) and knee are stabilized, then the hamstrings can act to anchor the sacrotuberous ligament which can help to stabilize the SI joint as well as anchoring the TLC.

Note that an alternative method for adding tension to the sacrotuberous ligament is to spread the sitting bones. This then helps to stabilize the sacroiliac joint.

Stabilizing The Thoracolumbar Composite via the TA

Since the thoracolumbar composite is made up of fused layers of the PRS, the erector spinae aponeurosis, fibers from the aponeurosis of the latissimus dorsai and since it also connects to the sacrotuberous ligaments, it can be an important anchor point for all of these structures. So that it can act effectively as an anchor tension can be added to it via activation of the lower fibers of the transverse abdominis.

This could be in concert with activation of the lumbar mulitifidus.

Pulling in on the ASICs and the inguinal ligament with the lower fibers of the TA will cause the PSIS to spread which the TLC resists. In the process, tension is added to the TLC. Thus it can help to act as an anchor for the aforementioned muscles.

Nutation is when the sacrum nods forwards relative to the hip bones. Counter nutation is the opposite movement, a nodding backwards.

Generally with nutation, the top of the sacrum moves forwards and the ASICs move inwards, reducing the size of the upper aperture of the pelvis. At the same time the bottom tip of the sacrum moves forwards and the ischial tuberosities inwards causing the diameter of the lower aperture of the pelvis to reduce.

In counter-nutation, the opposite occurs.

As the sacrum nods backwards, it moves slightly downards relative to the hip bones. The tailbone moves forwards and the ischial tuberosities inwards.

Meanwhile the top of the sacrum moves rearwards and the ASICs outwards.

The Transverse Abdominis and Nutation

In the region of the pelvis, the lower fibers of the transverse abdominus connects to the ASIcs and to the inguinal ligament which runs between the ASIc and the Pubic tubercle (close to or on the pubic bone.)

If these particular fibers of the Transverse Abdominus are activated, they create an inwards pull on the ASICs. This creates an outward moving force at the PSICs which is resisted by the thoracolumbar composite. As a result the sacrum nutates, nodding forwards, causing the Ischial tuberosities to spread apart.

To resist the force caused by the transverse abdominis, the pelvic floor muscles also activate. Together these muscles resist the outward movement of the Ischial tuberosities as well as the rearward movement of the bottom tip of the sacrum.

They don't necessarily prevent these movements, they just work against them. As a result, the SI joints are stabilized by the pelvic floor muscles and transverse abdominis and the fibers of the thoracolumbar composite working against each other.

The Pelvic Floor Muscles and Counter-nutation

The pelvic floor muscles are a group of muscles that can work together to varying degrees to create an inwards pull on the ischial tuberosities (or more precisely the ischial spines) while also creating a forward pull on the coccycx or tailbone, the bottom tip of the sacrum.

In combination with the multifidus, these muscles can be used to create sensations that feel like wagging the tailbone.

As already mentioned, they also work against the lower fibers of the transverse abdominis to help stabilize the SI joints.

If used to help counter nutate the sacrum, then these muscles can be resisted by the lower fibers of the transverse abdominis. They may also be resisted by activation of the lumbar multifidus which can act to pump up the thoracolumbar composite, thus resisting counter-nutation.

In this case, the job of transverse abdominis and multifidis isn't necessarily to prevent counter-nutation, but to resist is so that the SI joints are stabilized.

When flexing the spine (bending it forwards) the rear wall of the PRS is lengthened vertically while at the same time it gets thinner laterally.

Activating the Transverse Abdominus so that they pull inwards towards the spine, there may be a point, if enough tension is added, that a lateral pull is created on the PRS which then causes it to resist forward bending of the spine.

Stretching the fascia sideways makes it try to shorten longways.

Bending rearwards (extension) if the transverse abdominus are pulled inwards enough they could be used to help reduce the top to bottom length of the rear wall of the PRS thus assisting extension of the spine.

The Pump Up Phenomenon and the PRS

The PRS surrounds the spinal erectors in such a way that when they activate the sheath magnifies their effort. At the same time the sheath is pressurised by the activation and becomes more resistant to back bending.

And so one reason for activating the spinal erectors in a back bend (particularly in poses where gravity assists the back bend) is that the Pump Up action of the spinal erectors within the PRS helps to support or bolster the rear of the spine, reducing pressure on the rear part of the inter-vertebral discs.

The Pump Up Phenomenon and the Abdomen

Intra Abdominal Pressure (or IAP) can be created in front of the lumbar spine by contracting the respiratory diaphragm to presses down on the abdominal organs, contracting the pelvic diaphragm to resist the organs moving downwards and also contracting the transverse abdominus to pressurize the abdominal organs cirumferentially. The obliques and rectus abdominus can also take part in creating IAP. One reason for creating IAP is to brace the front of the spine.

While intra abdominal pressure can help to support the front of the spine, I'd suggest that a more important reason for Intra Abdominal Pressure is that it allows the respiratory diaphragm and transverse abdominis to work against each other.

Active muscles need an opposing force to work against in order to stay active.

If the diaphragm has an opposing force to work against then it can help to support the front of the lumbar spine by creating an upward pull on it via it's attachments there.

Since the diaphragm also has connections to the 12th rib and the kidneys which in turn connect to the psoas, diaphragmatic tension may also anchor the psoas which also attaches to the front of the lumbar vertebrae.

In either case, muscle tissue tension creates connective tissue tension which can be used to protect spinal joints.

The Transverse Abdominus wraps around the belly with horizontal fibers like a belt.

The upper bands fills the gap between the bottom of the ribcage and the top of the pelvis and attaches to the transverse processes of the lumbar spine via the Middle Layer of the thoracolumbar Fascia (MLF).

The lower span of the Transverse Abdominus attaches to the ASISs and inguinal ligament.

ASISs stands for Anterior Superior Iliac Spine. (I also sometimes use ASICs where the C stands for Crest as opposed to Spine). PSIS stands for Posterior Superior Iliac Spine. These pelvic landmarks mark the front and rear points of the crest of the pelvis respectively.

The inguinal ligament joins the ASISs to the pubic bone and creates the crease between lower belly and the top of the thigh.

The Spinal Erectors (or Erector Spinae) and Transverso Spinalis run up the back of the spine from sacrum to skull. Together these muscles can be referred to as the Paraspinalis. In the lumbar region the paraspinalis are made up of the Multifidus, Longissimus and Iliocostalis. The Aponeurosis of the Erector Spinae is common to all of them.

Aponeurosis is connective tissue similiar to tendon that connects a muscle to bone. It differs from fascia in that it has a consistent fiber direction for directing tension.

At the level of the sacrum the aponeurosis of the Spinal Erectors fuses to the overlaying deep and superficial laminas of the PLF.

PLF stands for Posterior Layer of the thoracolumbar Fascia. It actually consists of two lamina (another word for layer in my mind). The superficial lamina is the more rearward and closer to the surface lamina while the deep lamina is more forwards and closer to the center of the body.

In newer texts the deep lamina of the PLF in combination with the MLF tends to be called the Paraspinalis Rectinacular Sheath (PRS). Previous authors viewed the MLF and PLF as separate sheets of fascia that connected at the Lateral Raphe but newer models view the MLF and PLF as a single sheet of fascia which together with its connections to the spine create a tube for the paraspinalis muscles, the Paraspinalis Rectinacular Sheath.

The fused mass of connective tissue that results from the aponeurosis of the Spinal Erectors fusing to the PRS and to the superficial layer of the PLF is called the TLC or Thoracolumbar Composite. It connects the PSIS on both sides to each other as well as to the rear of the sacrum. It in turn connects to the Sacro-Tuberous Ligaments (STL) and via it to the long head of the Biceps Femoris.

The Gluteus Maximus (GM) attaches to rear surface of the TLC as well as to the sacrotuberous ligament. As such, tension in the TLC can serve as a foundation for the Gluteus Maximus. Or, tension from the Gluteus Maximus, contracting from the femur, can add tension to the TLC.

Fibers of the gluteus maximus combine with lower fibers from the contralateral (opposite side) latissimus dorsai. Both of these muscles can be thought of as belonging to the superficial lamina of the PLF.

The Quadratus Lumborum is a muscle located at the back of the body between the bottom of the ribcage and the top of the pelvis. From the crest of the ilium it connects to the transverse processes of the lumbar spine and to the bottom most ribs (rib number 12.)

At the lateral edge of the PRS, there is a seam of connective tissue called the Lateral Raphe which is where the Transverse Abdominus and Latissimus Dorsai makes contact. The fibers of the Transverse Abdominus then blend with the front wall of the PRS where it passes between the Paraspinalis and Quadratus Lumborum. The front wall, thicker because of the intermix of Transverse Abdominus fibers is sometimes referred to as the Middle Layer of the thoracolumbar Fascia or MLF.

Published: 2015 09 30

Updated: 2023 03 22