Sacroiliac Joint Stability during forward bending

Sacrotuberous ligament tensioning for resisting SI Joint shear in forward bends

It has been suggested that the Sacroiliac Joint can be vulnerable when doing forward bending yoga poses, particularly for people who are very flexible.

When doing a forward bend for the hips (say to stretch the hamstrings) at least one website suggests that the spine pulls the sacrum in one direction while the hamstring muscles pulls the pelvis in the other direction.

These opposing pulls may exert a lot of tension (or shear force) on the ligaments of the SI joint, potentially pulling it apart.

The suggestion is to bend the knees to reduce hamstring tension and thus reduce the shear force that may be acting on the Sacroiliac joint.

My own suggestion is to widen the sitting bones so that tension is added to the sacrotuberous ligament. This could be thought of as an "anti-mula bandha."

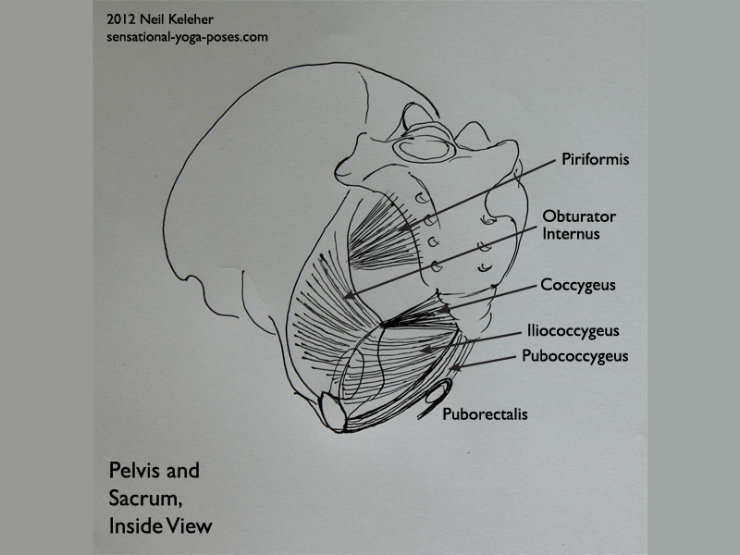

(In mula bandha, the pelvic floor muscles are used to pull the ischial spines inwards. Widening the sitting bones may be caused by the obturator internus muscle activating.)

The sacrotuberous ligament will then oppose this shear force.

The sacrum is a triangular bone at the back of the pelvis that joins the two halves of the pelvis.

It's like a downward pointing arrow that points to the anus. The tip of this arrow is formed by the tailbone.

Near the top of the sacrum on either side are two ear shaped surfaces. These twin surfaces connect to similarly shaped surfaces on either half of the pelvis to form the Sacroiliac joints.

These surfaces may not actually touch. Instead they are maintained in close relationship without actually contacting via the connective tissue that binds the sacrum to the pelvis. This non-contacting between the bones is may allow the sacrum to move relative to the pelvis while still maintaining the relationship with the pelvis.

Looking at the back edge of the pelvis, below the Sacroiliac joints and at about the level of the tailbone (just where it joins to the sacrum) are the ischial spines.

These points of bone protrude rearwards and slightly inwards at the back edge of the pelvis, just above the sitting bones.

Just above the ischial spine is the upper sciatic notch, the gap through which the piriformis passes as it attaches the sacrum to the thigh bone.

Below the ischial spine is the lower sciatic notch. This is where the obturator internus wraps around the back of the pelvis to attach to the thigh bone.

The piriformis reaches downwards from pelvis to thigh bone, the obturator internus slightly upwards.

The piriformis attaches to the front surface of the sacrum, more or less below the level of the SI joints. The obturator internus attaches to a large surface area on the inside of the pelvis. If you draw a line around the inside of the pelvis from the top of the sacrum to the top of the pubic bone, the obturator internus connects to most of the internal surface area of the pelvis below this line.

The two main sacroiliac ligaments are the posterior sacroiliac ligament and the anterior sacroiliac ligament. Both of these can easily be viewed as "webs" attaching at the rear and front of the SI Joint.

(It's like spiderman shot webs at the SI Joint from the front and rear to hold the pelvis and sacrum together.)

The pattern of webwork of these ligaments and the shape of the surfaces where the sacrum and pelvis meet may bear a resemblance to the sutures of the skull.

One team modeled the bones of the skull and the sutures that hold them together. They found that because of the network of sutures they couldn't press the bones of their model skull together, The bones where held in the same relationship without coming into contact. This could account for how the skull expands to account for the size of a growing brain.

The sacroiliac ligaments may act in a similiar way to keep the pelvis and sacrum from actually touching while maintaining their relationship.

Other ligaments also serve to reinforce these ligaments.

From the sitting bone, or ischial tuberosity there is a ligament called the sacrotuberous ligament that reaches upwards from the sitting bones to attach to the sides and rear of the sacrum.

Viewing the pelvis from the rear, these ligaments reach upwards and inwards from the pelvis to the sacrum, as it to form and upward pointing triangle.

With added tension they could possibly resist the sacrum being pulled upwards relative to the pelvis.

Another ligament, the sacrospinous ligament, attaches from the ischial spine to the tailbone. These ligaments reach down from the pelvis to the tailbone and could oppose the sacrum being pulled downwards relative to the pelvis.

The hamstring muscles (which run up the back of the thigh) attach to the sitting bones. Some fibers of the hamstrings are actually continuous with the fibers of the sacrotuberous ligament.

If the hamstrings are engaged or pulled tight and the position of the body is such that the hamstrings pull on the pelvis in one direction, while the spine and sacrum are pulled in the opposite direction, then tightening the sacrotuberous ligament may actually reduce or counteract the shear stress generated by these opposing movements, reducing or sharing some of the load on the posterior and anterior sacroiliac ligaments.

The pelvis is a flexible structure. The Sacroiliac joints is what helps to give the pelvis its flexibility.

One of the ways in which the pelvis can change shape is that the sitting bones can move away from each other. This movement could be accompanied by a rearward movement of the tailbone and bottom of the sacrum.

At the same time the sides of the top of the pelvis move inwards, particularly towards the front of the pelvis. The top of the sacrum moves forwards.

This movement can be consciously created by either causing the upper front of the pelvis to become narrower or by widening the sitting bones. If while standing, the thigh bones are held stable then the obturator internus muscle, which passes out the back of the pelvis just below the ischial spines, and just above the sitting bones, can potentially be used to widen the sitting bones, adding tension to the sacrotuberous ligament.

The sacrotuberous ligament may already be under a lot of tension during normal circumstances, so even a slight increase in the distance between sitting bones and sacrum may be enough to change the tension on this ligament.

This could be especially handy during forward bending so that instead of bending the knees to reduce hamstring tension you could work instead on widening the backs of the thighs and the sitting bones so that the tension on the sacrotuberous ligament is increased.

Then, even with the tension of the hamstrings pulling downwards (assuming a standing forward bend) on the sitting bones, the sacrotuberous ligaments would help to transmit some of that downwards pull to the sacrum also, resisting the shear force caused by the upper body pulling the spine out of the pelvis.

One other muscular connection should be mentioned here.

The gluteus maximus muscle has fibers that attach to the sacrotuberous ligament. (A more proper way to say it could be that part of the gluteus maximus is an extension of the fibers of the sacrotuberous ligament.) It also has fibers that attach to the rear of the sacrum.

By adding tension to the Sacrotuberous ligament, then the fibers of the gluteus maximus that attach to this ligament have a stable foundation from which to work on the thigh. These fibers can then assist in extending the thigh at the hip joint (in other words, swinging the thigh rearwards relative to the pelvis) or resisting flexion of the thigh at the hip joint.

In a standing forward bend, the hamstrings may resist being stretched because they are activating to prevent the pelvis from tilting forwards in a sort of fear response. (We aren't letting go because if we do, we won't be able to pull you back up again!) If the gluteus maximus is active, or has the potential to become active (because of the stability offered by a tightened sacrotuberous ligament) then the brain may release tension on the hamstrings.

And so widening the sitting bones may not only reduce shearing force on the si joint ligaments, it can also make it easier to bend forwards at the hips while standing.

To do a standing forward bend, without undue stress on the sacroiliac joint, stand with the feet roughly parallel (adjust the amount of turn-out or turn-in of your feet if you need to). Inward rotate the thighs so that the backs of the thighs move away from each other. Then work at widening the sitting bones. You may find that they lift automatically.

To help deepen your forward bend you can try pulling (or pushing) the pubic bone backwards between the top of your thighs.

For muscular balance see if you can make the tension on both sides of the pelvis and rear of the pelvis exactly the same.

Additional actions you can experiment with include pushing the tops of the thighs outwards or inwards.

As a side note, if you find that you get hip clicking, particularly while standing up from standing forward bends, in addition to widening the sitting bones, try using your pelvic floor muscles to pull the sitting bones inwards (and the tailbone forwards) without actually letting the sitting bones more inwards or the tailbone forwards. So pull the sitting bones inwards, but resist the action.

Published: 2020 08 14

Updated: 2021 01 29