First principles thinking

Applying first principles thinking to a system is a way of understanding the system in question.

It's a way of breaking that system down into building blocks. Depending on the end goal that break down can vary.

As an example the way that a doctor breaks down the body is going to be different than the way a user/operator of a body breaks it down.

This type of thinking can be applied to understanding how the knees work, so that we can use them (and control them) more effectively.

Being forced to learn about knee rotation

In the course of dealing with various knee injuries, I learned that the knees do indeed rotate and that we have muscles that control knee rotation. I further learned that these same muscles can actually be used to help improve flexibility. It took some figuring out though.

Muscles that control knee rotation

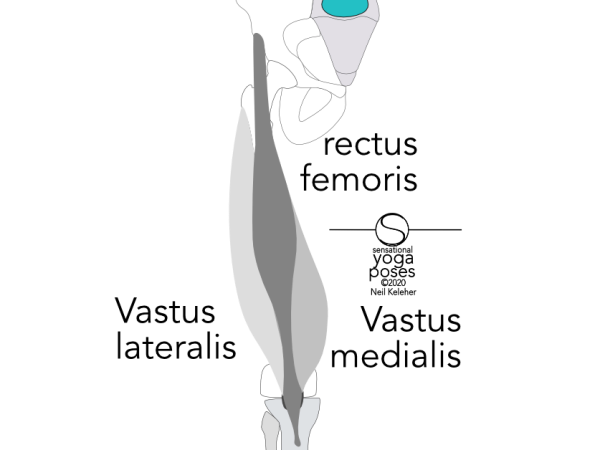

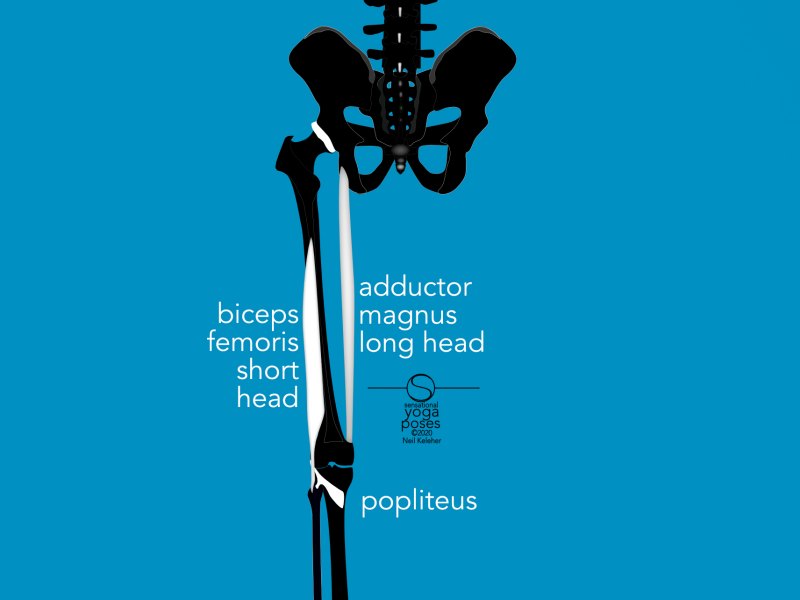

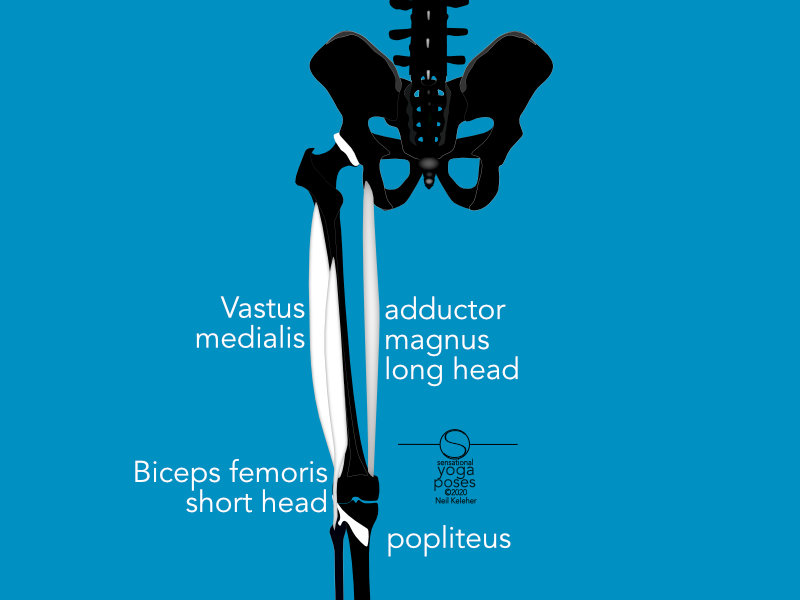

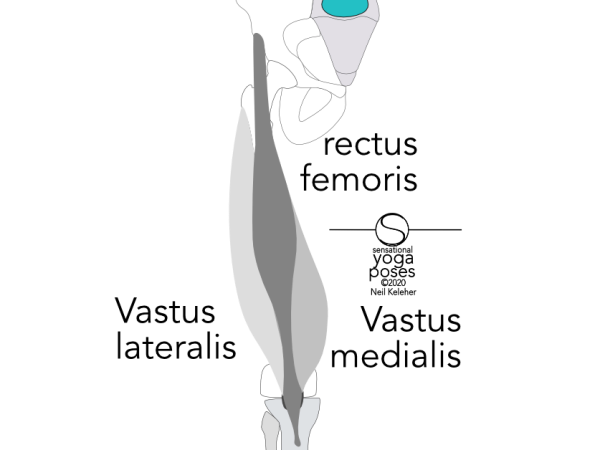

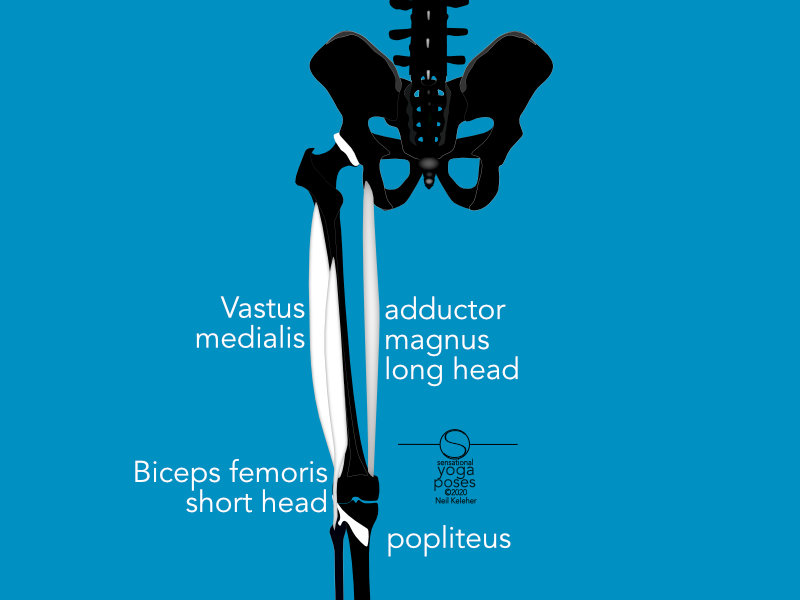

Single joint muscles that rotate the knee include the popliteus and biceps femoris short head at the back of the knee and two of the vastus muscles, vastus lateralis and vastus medialis at the front of the knee.

Front view of knee.

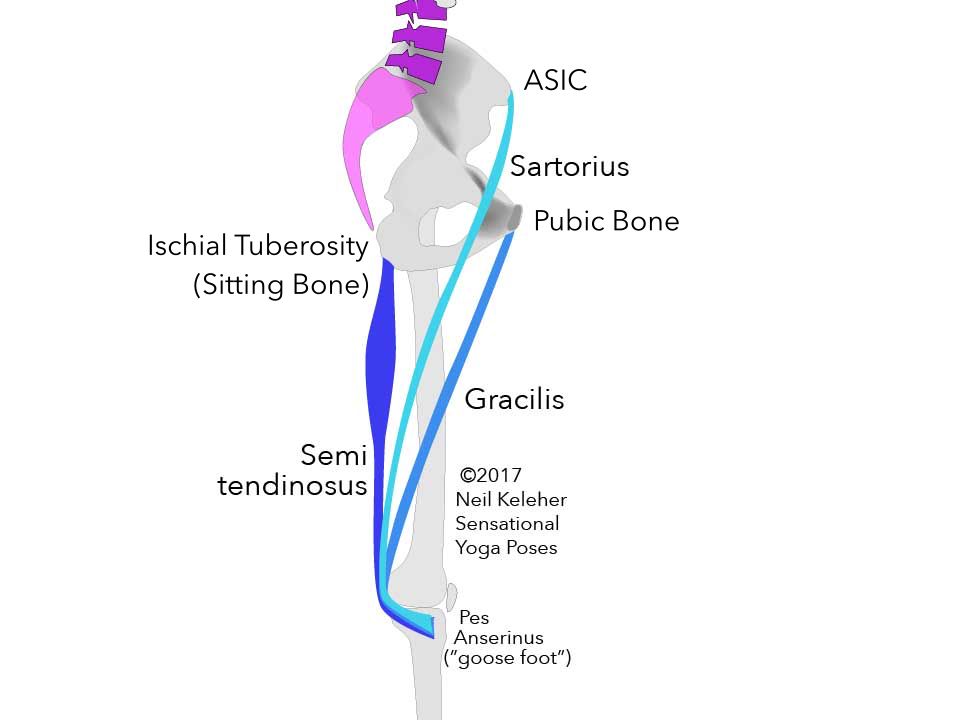

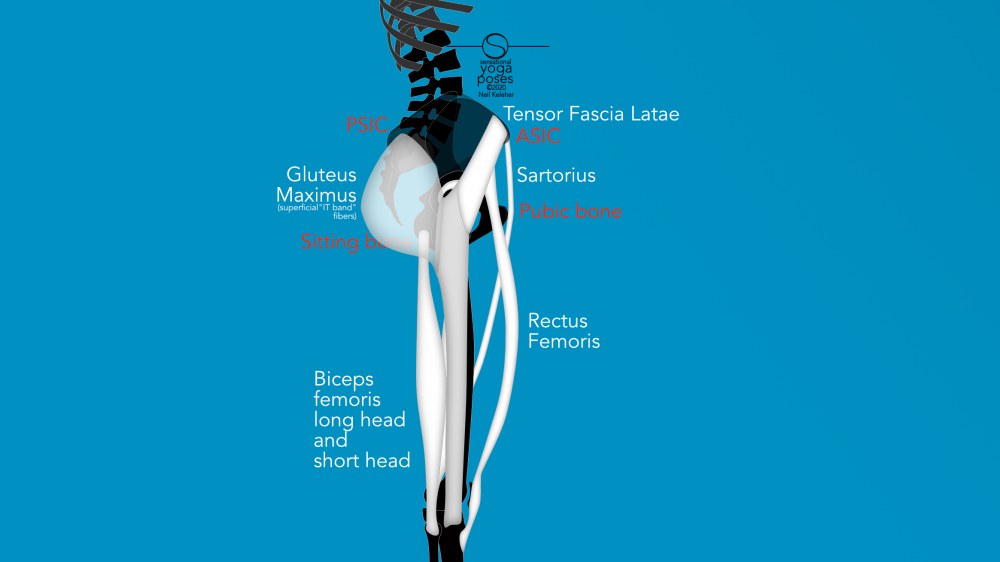

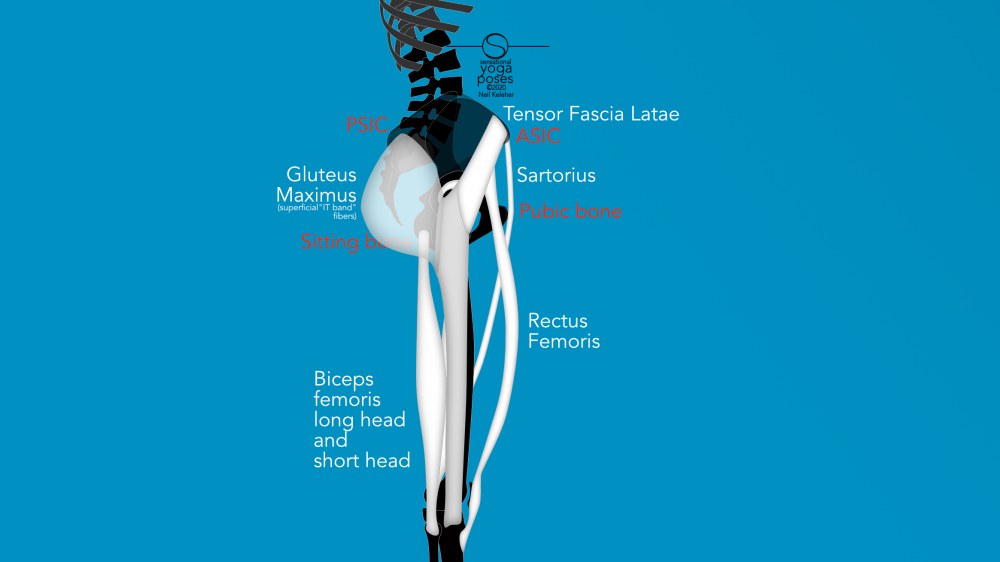

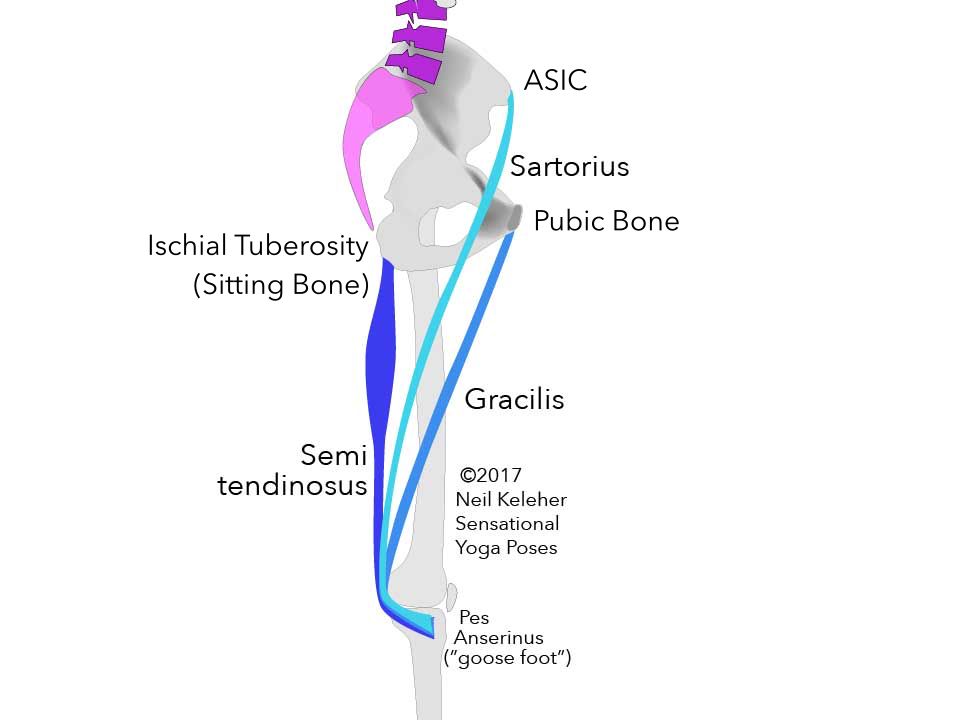

Multi joint muscles that rotate the knee and that attach to the hip bone include: tensor fascia latae, superficial gluteus maximus, biceps femoris long head, semitendinosus, gracilis and sartorius.

Side (lateral) view of knee and hip

Inside (medial) view of knee and hip

These muscles can collectively be termed the long hip muscles (though a better designation may be "long thigh muscles").

One multi joint knee rotator that attaches from the heel is the gastrocnemius.

Why are the knees designed to rotate?

One reason that the knees are designed to rotate is to transmit rotational torque from the hip to the foot and/or from the foot to the hip.

If the knee were simply a hinge joint with only muscles to drive flexion and extension, it probably wouldn't last very long if subjected to torque. The fact that the above mentioned muscles can be used to rotate the knee both internally and externally also means that these same muscles can help in transmitting torque through or past the knee joint without damaging it. Those multi joint muscles I mentioned (the long thigh muscles) can transmit torque directly from the hip bone to the shin or from the shin to the hip bone.

Anchoring the knee rotators for effective knee function

With respect to muscle control an important idea is that any muscle needs a fixed end point to act as a reference and so that it can act effectively on it's other end point.

For the single joint knee rotators, for them to activate and effectively stabilize against knee rotation or control knee rotation, they need to work from either a stable femur or a stabilized set of lower leg bones (the tibia and fibula).

And so when working to stabilize the knees by controlling knee rotation, or at least taking it into account an important point is to stabilize the femur against rotation at the hip joint. (Alternatively, the lower leg bones could be stabilized against rotation at the foot and ankle).

How do you stabilize the femur against rotation?

How do you stabilize the hip joint against rotation? In the absence of external forces or working against body weight, by using internal rotators (adductor magnus long head, gluteus minimus) against external rotators (gluteus maximus, obturator internus, quadratus femoris, piriformis).

Accounting for femoral twisting when stabilizing the femur against rotation

Because the femur is a long bone, it may be subject to twisting. And so if the femur is anchored against rotation at the top end but not at the bottom, any stabilizing affect may be lost due to twisting of the femur.

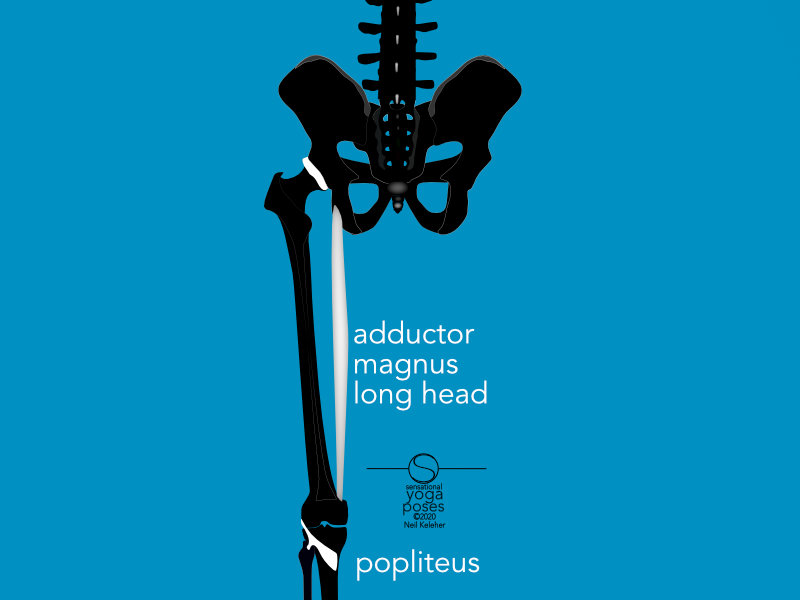

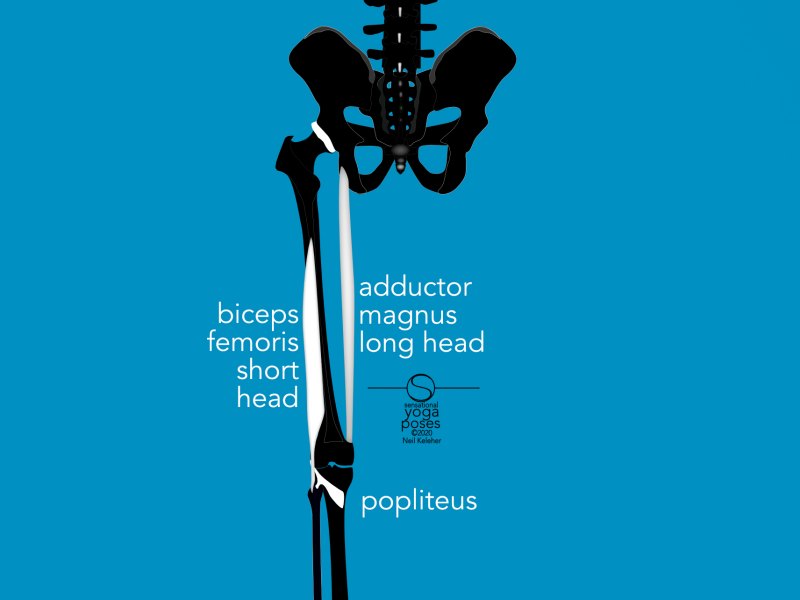

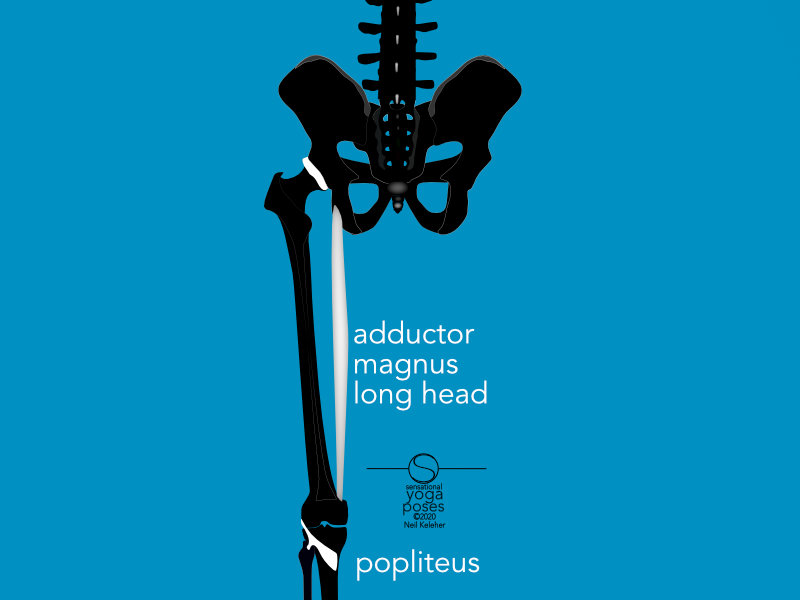

Rear view of knee.

One muscle that attaches near the bottom of the femur is the adductor magnus long head. Its upper end attaches to the sitting bone along with the hamstring muscles.

The adductor magnus long head works to rotate the femur internally, and in terms of stabilizing or controlling hip rotation it can work against the external rotation portion of the gluteus maximus.

Anchoring the VMO and popliteus muscles

An interesting point about the adductor magnus long head is that a portion of the vastus medialis called the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) attaches to it. If the adductor magnus is activated, then this muscle has a stable foundation from which to work on the knee.

Additionally, the attachment point of this muscle to the bottom of the femur is more or less directly opposite to the attachment point of the popliteus.

Rear view of knee and hip

Popliteus runs across the back of the knee to attach to the inside of the tibia from the outside of the bottom of the femur. So with the adductor magnus long head activated, not only can VMO activate, because it has a stable foundation, but so too can the popliteus.

In addition, the Vastus medialis proper can also activate.

Externally rotating the shin relative to the femur

Both of the aforementioned muscles may tend to cause an internal rotation force on the shin relative to the femur. A muscle that can cause an external rotation force on the shin relative to the femur is the biceps femoris short head muscle.

Vastus lateralis may also help to create an external rotation force on the shin relative to the femur.

Knee and hip, rear view.

Anchoring the shin against rotation at the knee

With the femur stabilized against rotation, VMO (as well as vastus medialis), popliteus, biceps femoris short head and vastus lateralis can work across the knee joint to stabilize the shin against rotation. They can thus help to stabilize the knee by controlling knee rotation.

With the lower leg bones rotationally stabilized, muscles that attach from the lower leg bones and run across the ankle to the bones of the feet also have a stable foundation from which to act.

Controlling shin rotation relative to the foot

When standing, these muscles can drive shin rotation relative to the foot.

Some would say that this is actually eversion and inversion of the foot, but while standing, these actions, with others, can cause shin rotation while at the same time causing the inner arch to lift or lower.

For more on this read foot exercises and/or fallen arches

Note the use of first principles thinking here. Rather than being restricted by labels like eversion and inversion, working from first principles allows us to come up with new movements as well as labels for those movements.

With the shins stable, these muscles can be used to stabilize the foot and ankle.

Stabilizing the shin against rotation from the ground up

The shin is actually made up of two bones, the tibia and fibula. When working from the ground up to stabilize against knee rotation from below and to transmit rotation from the foot to the hip, the muscle control required is a little more complex.

External rotation of the shin relative to the foot requires a rearwards pull on the fibula while internal rotation requires a forwards pull on it.

In addition, since the biceps femoris tends to create an upwards pull on the fibula, this needs to be resisted by a downwards pull on the fibula from the foot.

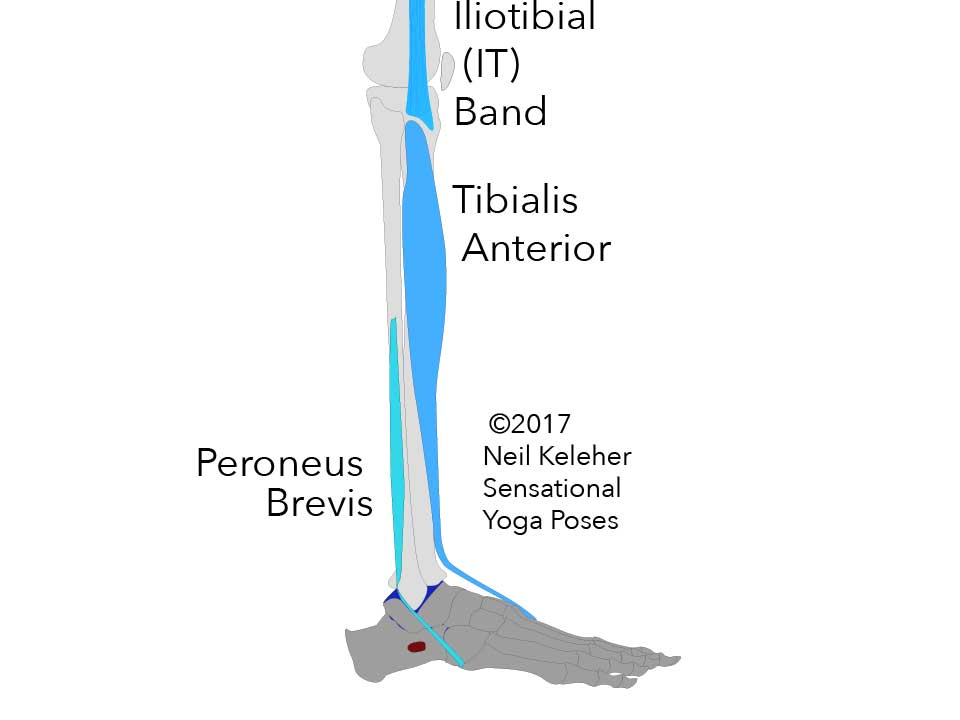

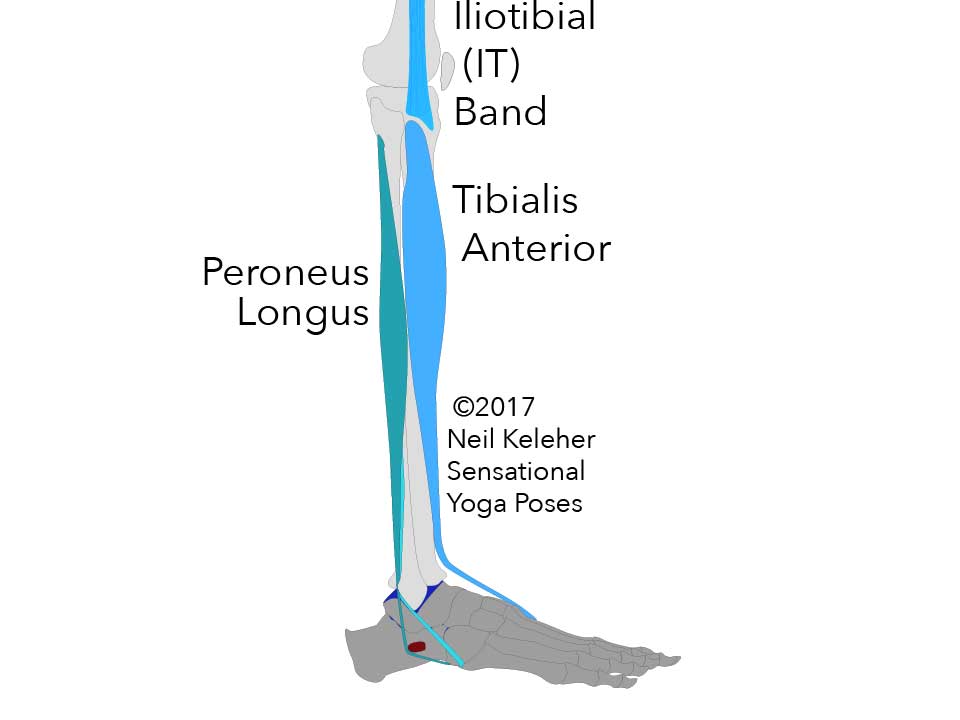

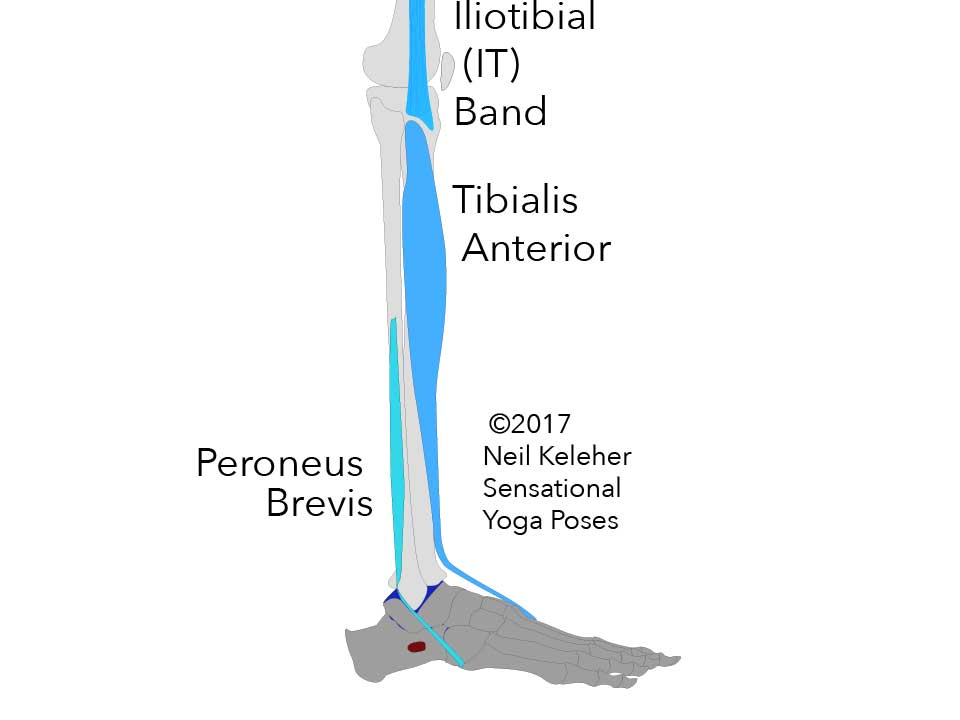

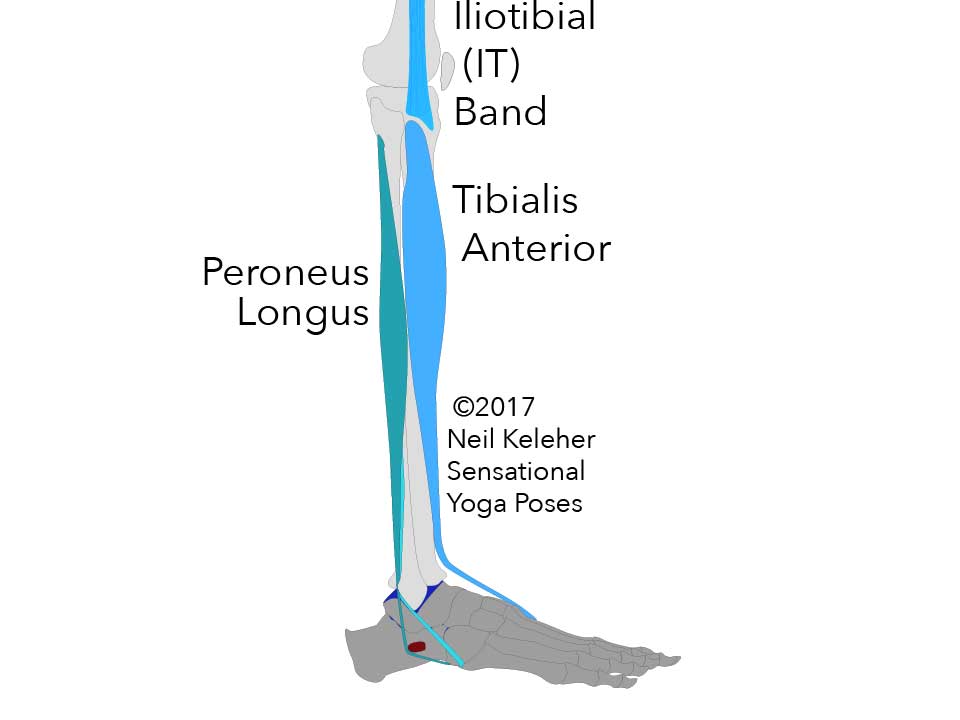

The importance of the peroneus brevis in stabilizing the foot

Where in hip rotation control the adductor magnus long head may be a key muscle, with shin rotation relative to the foot, one muscle that may be important to consider is the peroneus brevis. Because of its routing across the ankle, it tends to create a rearwards pull on the fibula while peroneus longus tends to create a forwards pull.

Lower leg, side view

Lower leg, side view

Note an interesting correspondance. Where the Tensor fascia latae and superficial gluteus maximus can work against each other to create a balanced pull on the IT band, the peroneus brevis and longus could work together to create a balanced pull on the fibula.

Stability and control is created by using opposing muscles against each other

Shin rotation not only tends to cause the arch to lift or lower, it also affects the heel bone. External shin rotation relative to the foot while standing tends to cause the heel to tip to its outer edge while internal rotation tends to cause the heel to tip to its inner edge.

For adductor magnus long head to activate in the absence of an external force it needs to work against the gluteus maximus and other external rotators. Failure of the gluteus maximus to activate against external rotation may be due to the fact that the adductor magnus long head isn't functioning for whatever reason.

In a similiar way, peroneus brevis activation may help to resist other shin rotation muscles in such a way that they can work against each other to stabilize or control shin rotation as well as helping to stabilize the heel (and ankle) against tilting.

First principles: applying understanding in different ways

So the focus so far has been on rotation of the joints of the leg, how it is caused and how it is controlled. Something that working from first principles allows is the application of understanding in different ways.

As an example of this, when I injured my knee, I still had to teach. But my knee was painful whenever I put weight on it. I learned what how to operate my muscles in such a way that my leg wasn't painful when I put weight on it. What I accidentally learned to do was control my knee rotators. I then found that this same control was useful in improving flexibility.

Muscles that control knee rotation as well as hip function

The long thigh muscles I mentioned previously not only help to control shin rotation, they can also be used to flex, extend, abduct or adduct the hip as well as help rotate it internally and externally.

And of course they can be used to stabilize against these actions or control them.

Two basic types of active stretching are active resisted stretching and active assisted stretching. In the former, the muscle being stretched is activated to resist the stretch while in the later the muscles that oppose the muscle being stretched are activated to drive the stretch.

Applying an understanding of knee rotation to improving flexibility and strength

What I learned was how to stabilize the knee against rotation so that I could use the long thigh muscles to either resist or assist hip flexion or extension. My forward bending improved as a result, as did my ability to do the splits.

Note that these long thigh muscles include adductors and abductors and so I've also used them to help me approach side splits.

And I also use an awareness of knee/hip/shin rotation when doing weighted exercises like squats.

The really cool thing is that through all of this experience I've learned that muscles not only move and control the body, they also help to drive proprioception. As a result, these are all actions that can be felt as well as controlled.

And that's pretty much what I focus on teaching in my classes as well as practicing when I'm doing my own practice.

Knee rotation limitations

As a final note I should point out here that when the knees are straight or only slightly bent, knee rotation tends to be limited. This doesn't mean that the muscles that control knee rotation suddenly switch off. Knee rotation control can be just as important when the knees are straight because it can help to make the knees stable.

Using an understanding of knee rotation to keep your knees safe

Another point about knee rotation (and what might be thought of as knee "side-bending") is that it allows us to do poses like virasana (kneeling with butt between the heels) and lotus pose (whether putting both legs in lotus, or only one as in half bound yoga lotus pose).

If you understand knee rotation and how to control it, you can apply that understanding to approaching poses like this (and other poses like the cosack squat) so that you can do them in such a way that your knees stay safe. That generally means using the muscles that control rotation of the hip, knee and ankle, and giving them a stable foundation from which to act.

Published: 2016 01 08

Updated: 2021 02 09